Maxim Forgets the Maxim, Chases Nuclear but Bombs

Maxim Media, the publishers behind the well-known men’s lifestyle magazine and brand MAXIM, had minimal success when in Maxim Media Inc. v Nuclear Enterprises Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1443 they sought urgent Federal Court orders to shut down an Australian company allegedly riding on their name — through magazines, domain names, destination tours, and model management services.

Maxim Media, the publishers behind the well-known men’s lifestyle magazine and brand MAXIM, had minimal success when in Maxim Media Inc. v Nuclear Enterprises Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1443 they sought urgent Federal Court orders to shut down an Australian company allegedly riding on their name — through magazines, domain names, destination tours, and model management services.

Despite the explosive accusations, the Court delivered a much more subdued response.

Maxim had delayed for some time in coming to Court, but now applied for interlocutory relief, seeking immediate injunctions to restrain:

-

Use of the MAXIM name in any form in Australia;

-

Distribution of a competing Maxim Magazine;

-

Operation of maxim.com.au, destinationmaxim.com.au, and related social handles;

-

Any further unauthorised brand use.

The application relied on trade marks registered in 2020 and 2023 — and on allegations that the Australian respondents, including Nuclear Enterprises and Michael Downs, had no licence or authority to use the name.

Justice Rofe refused the injunction — not because the claim was doomed, but because:

-

Ownership and licensing rights hadn’t been clearly established yet;

-

There were substantial factual disputes that needed a full trial;

-

There was no persuasive case for irreparable harm that couldn’t be remedied later;

-

The balance of convenience didn’t justify urgent intervention — particularly given Maxim’s delay in seeking relief (ironically, Maxim had ignored the equitable maxim regarding laches).

The proceeding will now be allocated to a docket judge for a full hearing.

The main takeaways here are:

-

Interlocutory relief isn’t automatic, even with a registered trade mark — the applicant still needs clean title, urgency, and evidence of irreparable harm.

-

Delays hurt. The longer you wait to challenge a rival’s use of your mark, the harder it is to convince a court that urgent action is needed.

The case could still blow Maxim’s way at a final hearing — but for now, Nuclear gets to keep exploding – and the fallout will be huge.

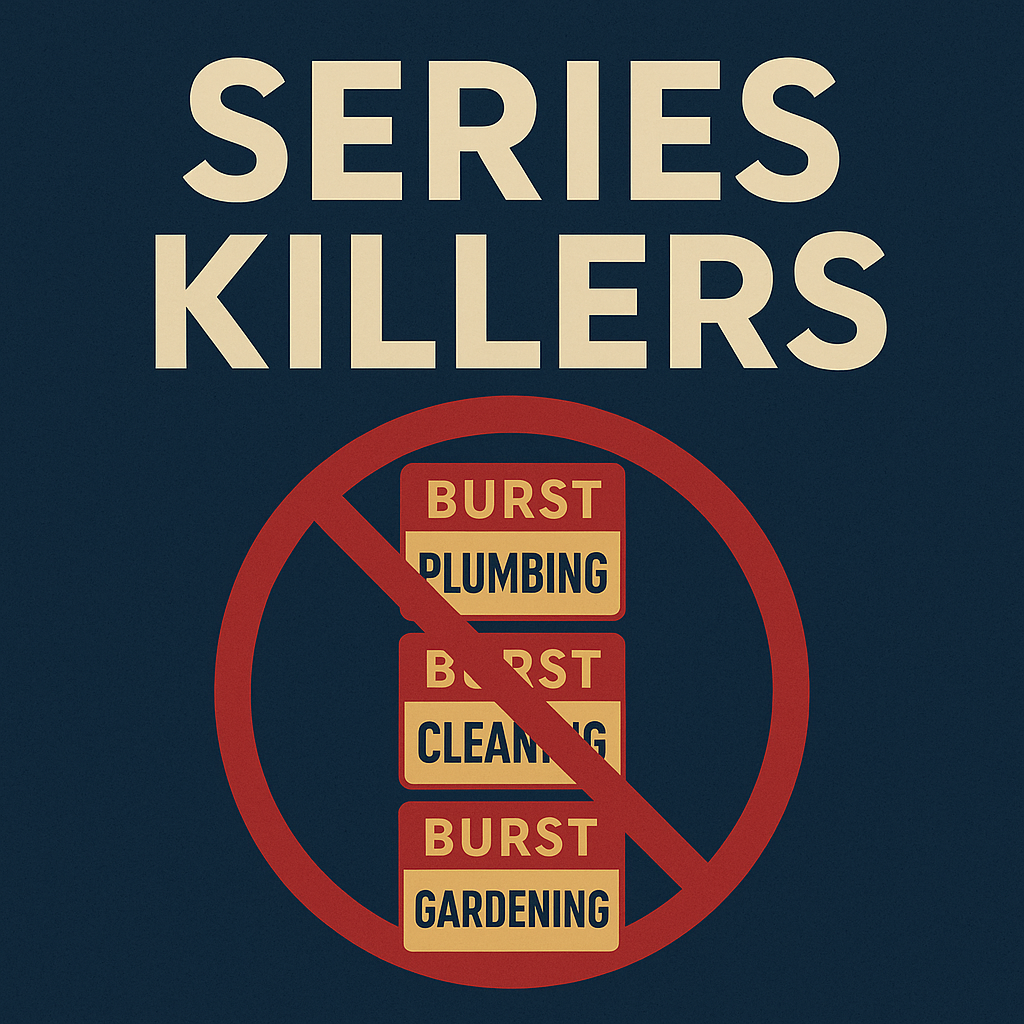

So you’ve filed a series trade mark in Australia. The marks are visually identical except for a single word that tweaks the service type — say, “BURST PLUMBING”, “BURST CLEANING”, “BURST GARDENING”.

So you’ve filed a series trade mark in Australia. The marks are visually identical except for a single word that tweaks the service type — say, “BURST PLUMBING”, “BURST CLEANING”, “BURST GARDENING”.

For many years, privacy enforcement in Australia was a bit… polite. The OAIC could nudge, issue determinations, and make a bit of noise, but it often lacked the real teeth needed to drive compliance in the boardroom. That era is over.

For many years, privacy enforcement in Australia was a bit… polite. The OAIC could nudge, issue determinations, and make a bit of noise, but it often lacked the real teeth needed to drive compliance in the boardroom. That era is over. Before the amendments to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) on 11 December 2024, if your Australian business wanted to send personal data overseas — say, to a CRM hosted in the US or a support centre in Manila — you had to jump through a slightly vague hoop. Under APP 8.1, you were supposed to take “reasonable steps” to ensure the recipient wouldn’t do anything that would breach the Australian Privacy Principles. And if they did? Thanks to section 16C, you were still on the hook.

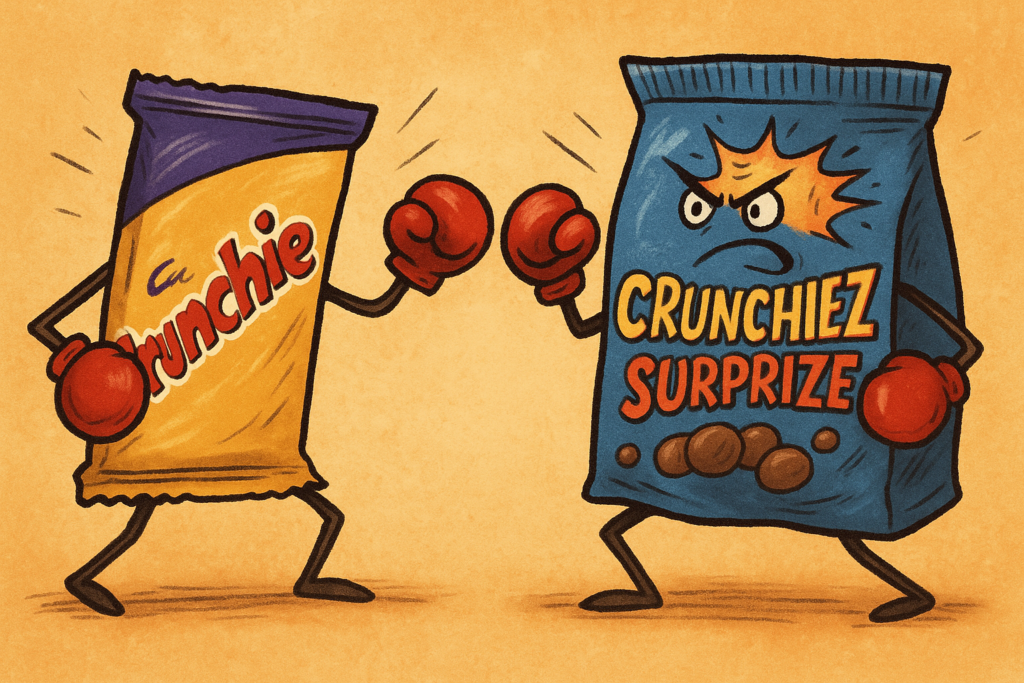

Before the amendments to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) on 11 December 2024, if your Australian business wanted to send personal data overseas — say, to a CRM hosted in the US or a support centre in Manila — you had to jump through a slightly vague hoop. Under APP 8.1, you were supposed to take “reasonable steps” to ensure the recipient wouldn’t do anything that would breach the Australian Privacy Principles. And if they did? Thanks to section 16C, you were still on the hook. In a sweet victory for brand owners, Cadbury UK Limited has successfully opposed the registration of the trade mark CRUNCHIEZ SURPRIZE in Australia, convincing the Trade Marks Office that the name was too close for comfort to its iconic CRUNCHIE mark.

In a sweet victory for brand owners, Cadbury UK Limited has successfully opposed the registration of the trade mark CRUNCHIEZ SURPRIZE in Australia, convincing the Trade Marks Office that the name was too close for comfort to its iconic CRUNCHIE mark.