🏇 When the Race Stops a Nation — Who Owns the Moment?

IP and brand lessons from Melbourne Cup Day

IP and brand lessons from Melbourne Cup Day

Every year on the first Tuesday in November, Australia stops for a horse race — and an extraordinary showcase of intellectual property.

Behind the glamour of Flemington, the fascinators and the flutter, lies a multi-layered web of IP rights: trade marks, designs, broadcast rights, sponsorships, licensing deals, and image rights that turn the Cup into one of the country’s most valuable event brands.

1. The Cup as a brand

The Victoria Racing Club (VRC) owns an extensive portfolio of trade marks covering “Melbourne Cup”, “The Race That Stops a Nation”, and the stylised gold trophy design. Those marks underpin everything from official merchandise to broadcast and hospitality rights.

For the VRC, it’s not just a horse race — it’s a global brand, protected by careful registration, licensing and enforcement. The lesson for other major events? File early, file broad, and police consistently.

2. Who owns the horse’s name?

When a horse becomes famous — Think Winx, Black Caviar, Makybe Diva — the name itself becomes valuable IP. Owners often move quickly to register trade marks covering racing merchandise, breeding rights, and promotional uses.

But racehorse naming rules also complicate matters: under Racing Australia’s rules, a horse’s name is licensed rather than owned, and certain names (of champions, or those with cultural significance) are permanently retired. That means an owner’s branding ambitions must navigate both trade mark law and the racing registrar’s strictures.

3. Passing off and false endorsement

Every Cup season brings a flurry of betting apps, sweep generators, and corporate promotions trying to ride the coattails of the “Cup” brand. Some risk drifting into misleading or infringing territory — using “Melbourne Cup” or the trophy image without authorisation.

It’s a classic passing-off risk: implying a connection or endorsement that doesn’t exist. The same principle applies beyond racing — whether your brand is invoking a festival, a celebrity, or a social movement, the question is always: does your use suggest official connection?

4. Fashions on the field — designs and branding

Even the fashion stakes come with IP issues. Designers rely on copyright, design registration, and branding to protect original pieces and accessories that debut trackside. Increasingly, brands run their own protected pop-ups and virtual events — blurring physical and digital rights.

5. Modern twists: influencers and digital IP

Today, Cup-day marketing spills across Instagram and TikTok. Influencers tag official partners, brands push instant content, and deepfakes and AI imagery are starting to creep in. For rights-holders, monitoring unauthorised digital use (and generative reproductions) has become the new frontier of event IP protection.

Take-away for brands and advisers

-

Register broadly: secure word, logo and shape marks early — even for event slogans.

-

Control use: structure sponsorships, broadcast and influencer agreements with precise IP clauses.

-

Monitor aggressively: unauthorised “association” can dilute event value fast.

-

Think digital: protect imagery, NFTs, and virtual activations just as you would physical goods.

The Melbourne Cup may stop the nation — but the IP behind it never sleeps.

Over the weekend the Australian Government finally drew a line in the sand: no special copyright carve-out to let AI developers freely train on Australians’ creative works. In rejecting a broad text-and-data-mining (TDM) exception, the Attorney-General signalled that any reform must protect creators first, and that “sensible and workable solutions” are the goal. Creators and peak bodies quickly welcomed the stance; the TDM exception floated by the Productivity Commission in August met fierce resistance from authors, publishers, music and media groups.

Over the weekend the Australian Government finally drew a line in the sand: no special copyright carve-out to let AI developers freely train on Australians’ creative works. In rejecting a broad text-and-data-mining (TDM) exception, the Attorney-General signalled that any reform must protect creators first, and that “sensible and workable solutions” are the goal. Creators and peak bodies quickly welcomed the stance; the TDM exception floated by the Productivity Commission in August met fierce resistance from authors, publishers, music and media groups.

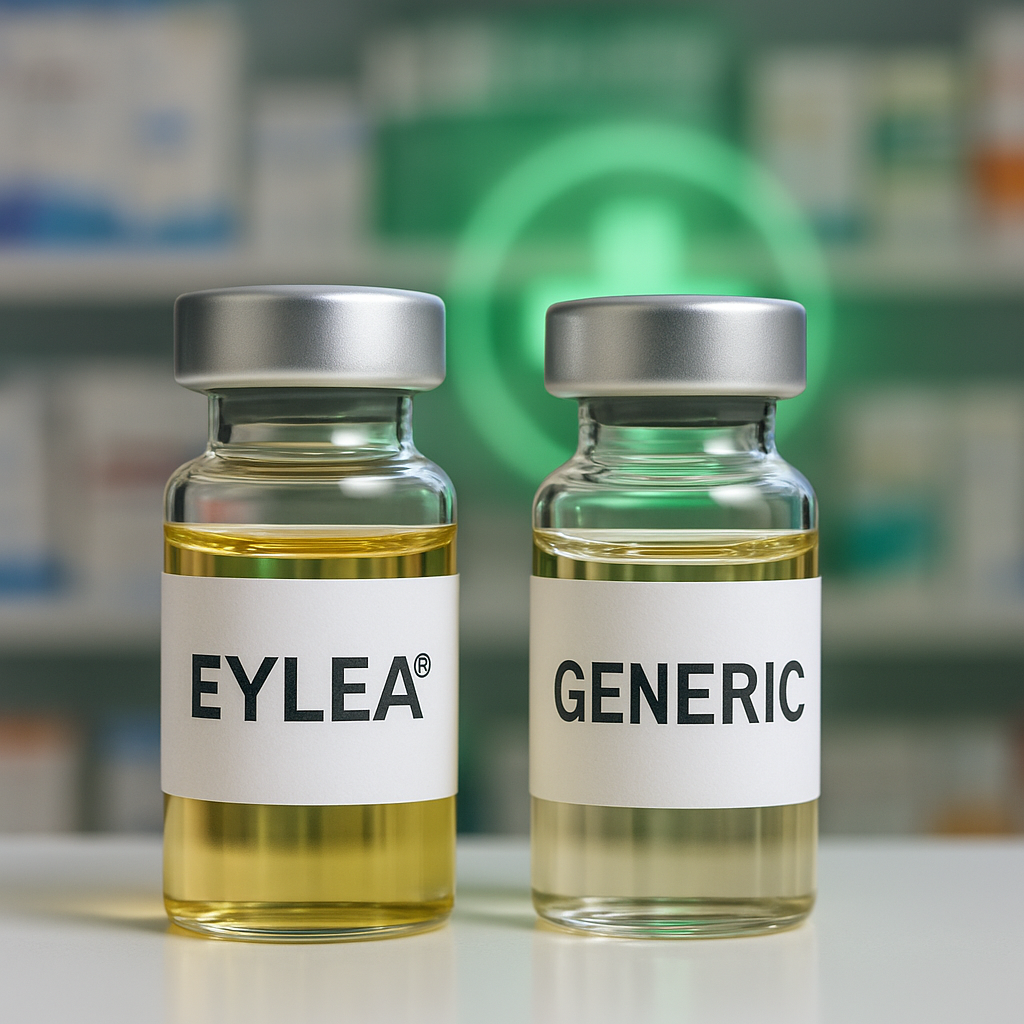

A Federal Court decision has just reshaped the battlefield for biosimilars in Australia.

A Federal Court decision has just reshaped the battlefield for biosimilars in Australia.

In

In