The Art of Disclaimers: Jacksons v Jackson’s Art Supplies (No 2)

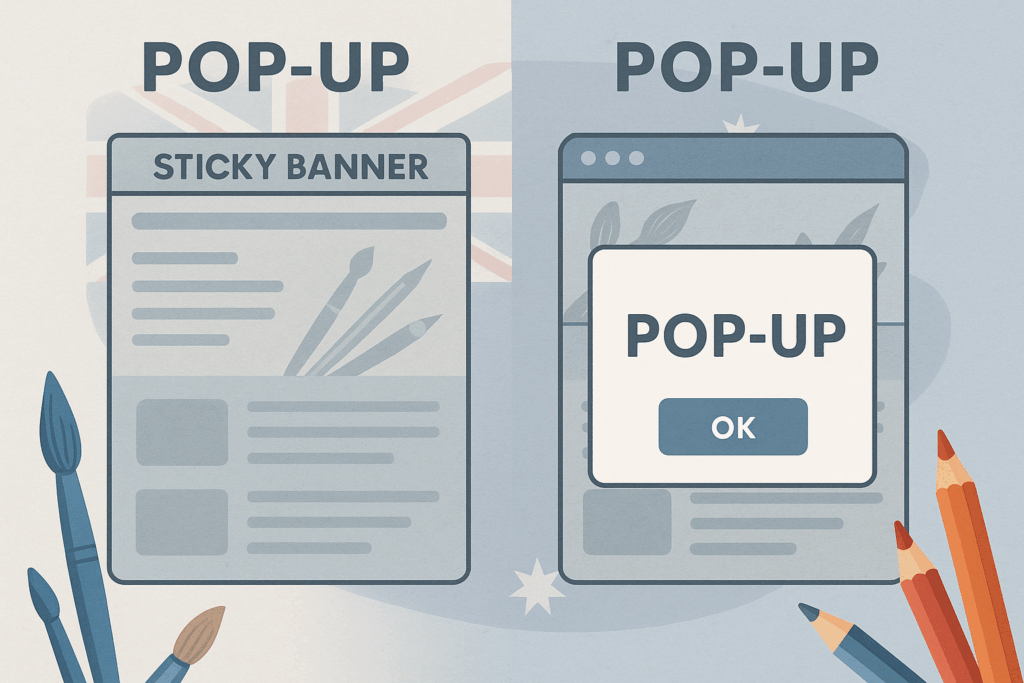

When two businesses with nearly identical names lock horns, things usually come down to trade marks, passing off, and reputation. But in Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd v Jackson’s Art Supplies Ltd (No 2) [2025] FCA 1127, the real fight was over disclaimers, pop-ups, sticky banners, and user attention spans.

When two businesses with nearly identical names lock horns, things usually come down to trade marks, passing off, and reputation. But in Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd v Jackson’s Art Supplies Ltd (No 2) [2025] FCA 1127, the real fight was over disclaimers, pop-ups, sticky banners, and user attention spans.

Yes, really. Welcome to the future of injunctive relief.

The Backdrop: Two Jacksons, One Internet

-

Jacksons Drawing Supplies (JDS) is the long-standing Australian art supply brand.

-

Jackson’s Art Supplies (JAS) is a UK giant with a strong online presence.

When JAS launched its Australia-specific subdomain (jacksonsart.com/en-au), it didn’t just sell paints and brushes — it displayed Australian flags, quoted in AUD, listed an Adelaide warehouse, and even had an Aussie phone number. To many customers, it looked like the local Jacksons.

The Court (in an earlier decision) held that this conduct contravened s 18 and s 29 of the ACL and amounted to passing off.

Round Two: The Relief Hearing

The question was: what form should the non-pecuniary relief take?

JDS wanted a sticky header disclaimer on every page (always visible). JAS wanted a one-off pop-up disclaimer (dismiss it once and never see it again).

The Federal Court, armed with expert evidence on digital attention, split the difference.

Attention Science Hits the Federal Court

This case is remarkable for its reliance on attention science experts:

-

Michael Simonetti (website developer & SEO expert)

Warned about “banner blindness”: users ignore sticky headers and disclaimers that look like ads. -

Dr Karen Nelson-Field (global expert on omnichannel attention science)

Explained that pop-ups trigger active attention because they interrupt the browsing experience. Sticky headers, by contrast, fade into the background. -

Professor Mingming Cheng (digital marketing & SEO)

Highlighted that hyperlinking to JDS’s site could affect search engine algorithms and reinforce associations between the two brands.

The Court accepted that no disclaimer format guarantees it will be read, but opted for the solution most likely to cut through.

The Court’s Orders

Justice Jackson ordered that JAS can’t operate its Australia-specific site (or any site with Australian characteristics) unless it shows a disclaimer:

“Please note: this website is not affiliated with the Australian company Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd or its website jacksons.com.au.”

The disclaimer must:

-

Pop up every time a user starts a new browser session, blocking the site until acknowledged.

-

Also appear at the bottom of each page (non-sticky, same size as body text).

-

Be clear, prominent, and legible.

-

Not include any hyperlink to JDS’s site (too much risk of SEO crossover and confusion).

No requirement for phone sales, social media, or ads — because the misrepresentation arose via the website itself.

No Sticky Business

JDS’s sticky header idea was rejected as:

-

Too intrusive, especially on mobile devices.

-

Likely to be ignored due to banner blindness.

-

Damaging to user experience with little benefit.

Pop-ups, despite being annoying, were judged the least-worst option.

Costs: Calderbank Offers Bite Back

The Court also tackled costs.

-

JDS was successful overall, but lost against the third and fourth respondents.

-

JAS had made Calderbank offers (including restricting sales into JDS’s “core markets” and paying a small sum).

-

The Court held JDS was not unreasonable to reject them — the offers didn’t resolve the cross-claim, lacked mutuality, and wouldn’t necessarily prevent consumer confusion.

The result?

-

JDS gets costs against the first and second respondents (with a 15% discount).

-

The third and fourth respondents get indemnity costs from a certain date.

Why This Case Matters

This decision is a practical playbook for how courts may deal with online misrepresentation and passing off in 2025 and beyond:

-

Disclaimers must do more than exist — they must grab attention. Passive banners won’t cut it.

-

User experience is relevant — remedies must be proportionate and fair, not ruin the site.

-

Hyperlinks aren’t a free fix — they can create new risks of association in both consumers’ minds and search engine algorithms.

-

Attention science is evidence — expert testimony on human behaviour online now shapes equitable relief.

-

Calderbank strategy remains vital — but offers must be clear, mutual, and genuinely address the issues at stake.

Takeaways for Brand Owners

-

Global websites need local strategy. If you’re running an AU subdomain, check your disclaimers and branding.

-

Disclaimers aren’t window dressing. Courts will look at how they’re delivered, not just what they say.

-

Attention matters. Evidence from digital marketing and psychology can sway the outcome.

-

Settlement strategy is as important as trial strategy. Get your Calderbank offers right.

Bottom line: The Federal Court has signalled that in the age of pop-ups, banner blindness, and Google algorithms, effective remedies must be technologically and behaviourally savvy. For IP lawyers and brand managers, Jacksons v Jackson’s is a reminder that protecting reputation online requires more than just words — it requires understanding how consumers really pay attention.

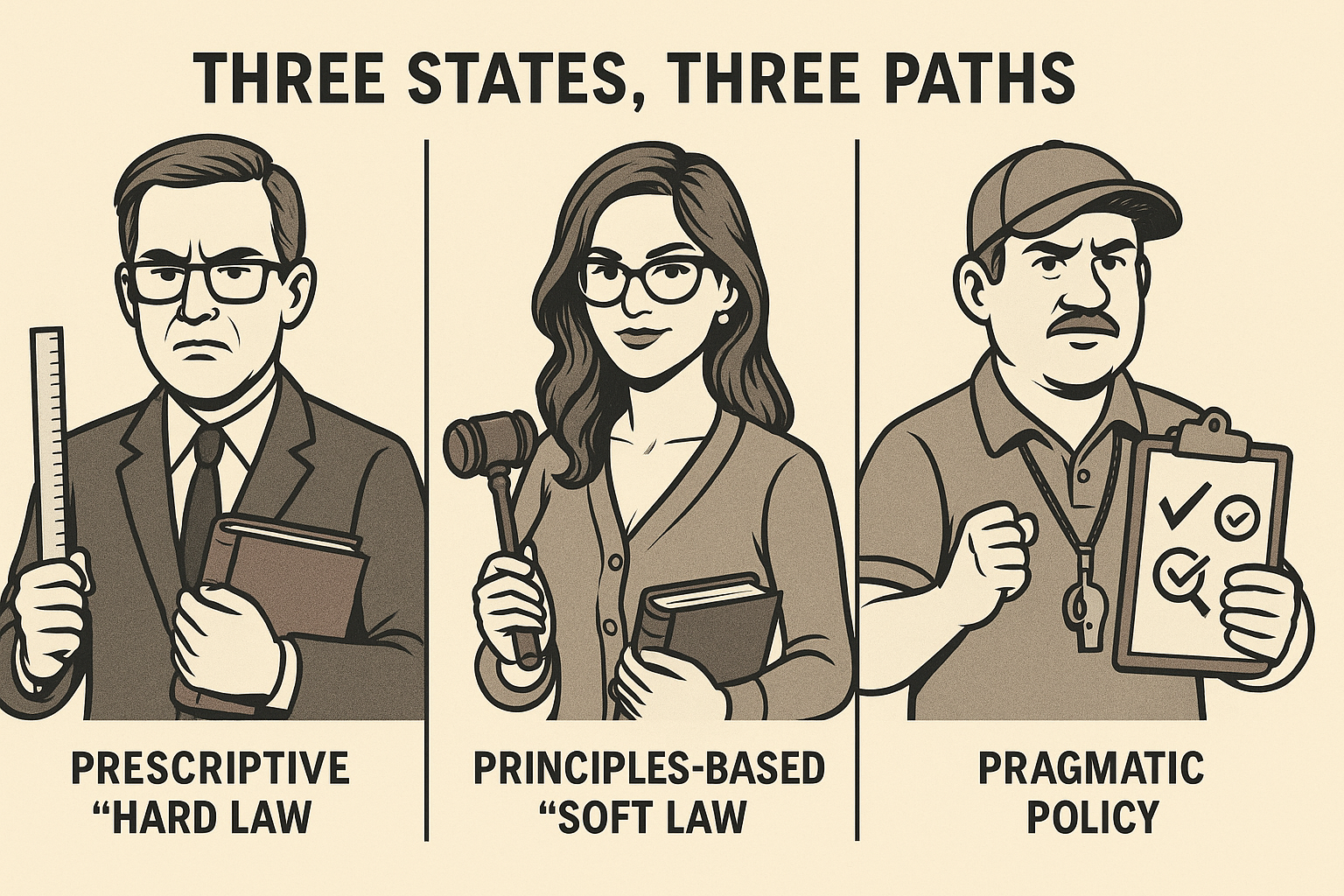

Australia’s courts are no longer sitting on the sidelines of the AI debate. Within just a few months of each other, the Supreme Courts of New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland have each published their own rules or guidance on how litigants may (and may not) use generative AI.

Australia’s courts are no longer sitting on the sidelines of the AI debate. Within just a few months of each other, the Supreme Courts of New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland have each published their own rules or guidance on how litigants may (and may not) use generative AI. From ChatGPT hallucinations to deepfakes in affidavits, Queensland’s courts have drawn a line in the sand.

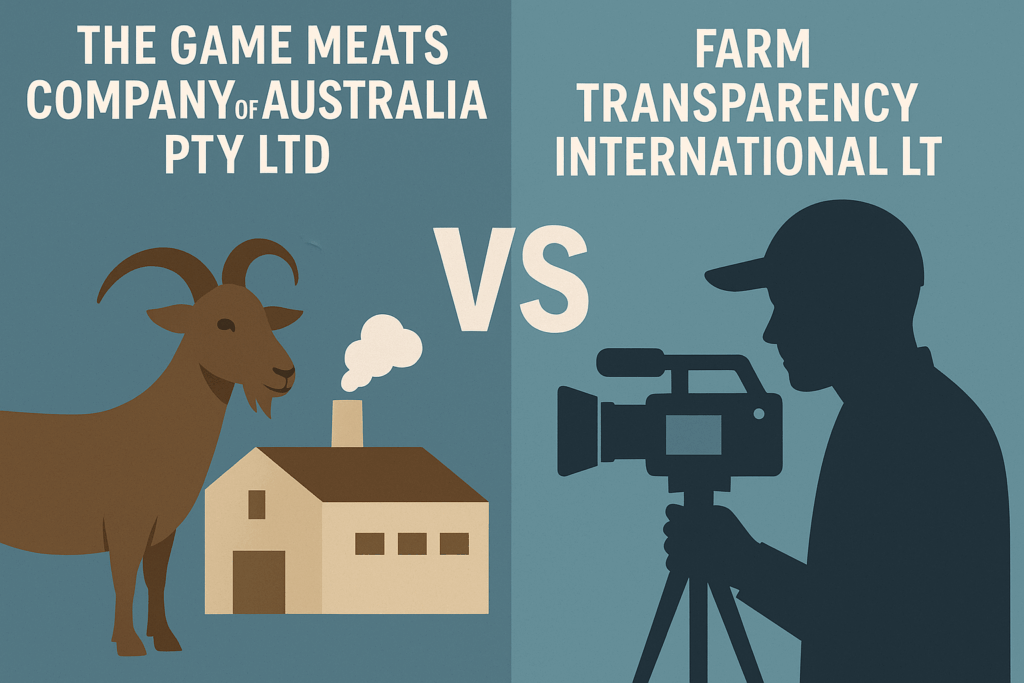

From ChatGPT hallucinations to deepfakes in affidavits, Queensland’s courts have drawn a line in the sand.  When animal rights collide with copyright law, sparks fly — and sometimes, whole new branches of doctrine get tested.

When animal rights collide with copyright law, sparks fly — and sometimes, whole new branches of doctrine get tested. If you thought plumbing valves were boring, think again.

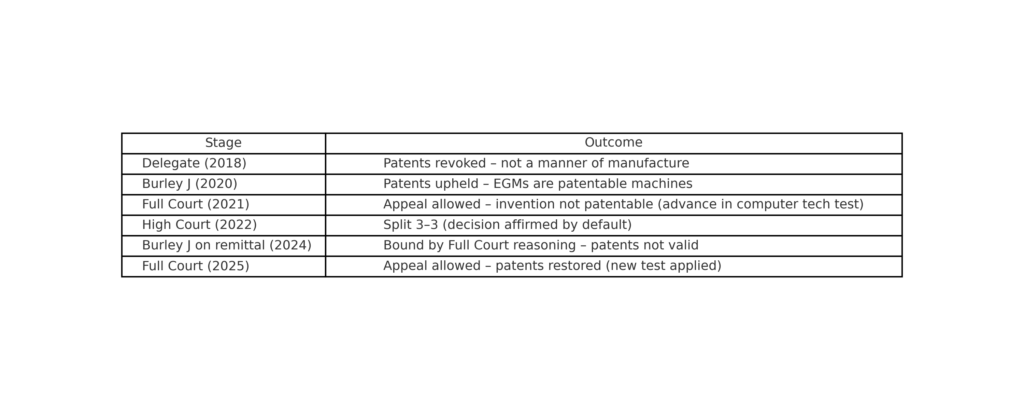

If you thought plumbing valves were boring, think again. When does a slot machine cross the line from an abstract idea to a patentable invention?

When does a slot machine cross the line from an abstract idea to a patentable invention?  Cue the latest appeal.

Cue the latest appeal.