AI Training in Australia: Why a Mandatory Licence Could Be the Practical Middle Ground

Over the weekend the Australian Government finally drew a line in the sand: no special copyright carve-out to let AI developers freely train on Australians’ creative works. In rejecting a broad text-and-data-mining (TDM) exception, the Attorney-General signalled that any reform must protect creators first, and that “sensible and workable solutions” are the goal. Creators and peak bodies quickly welcomed the stance; the TDM exception floated by the Productivity Commission in August met fierce resistance from authors, publishers, music and media groups.

Over the weekend the Australian Government finally drew a line in the sand: no special copyright carve-out to let AI developers freely train on Australians’ creative works. In rejecting a broad text-and-data-mining (TDM) exception, the Attorney-General signalled that any reform must protect creators first, and that “sensible and workable solutions” are the goal. Creators and peak bodies quickly welcomed the stance; the TDM exception floated by the Productivity Commission in August met fierce resistance from authors, publishers, music and media groups.

So where to from here? One pragmatic path is a mandatory licensing regime for AI training: no free use; transparent reporting; per-work remuneration; and money flowing to the rightsholders who opt in (or register) to be paid. Below I sketch how that could work in Australia, grounded in our existing statutory licensing DNA.

What just happened (and why it matters)

-

Government position (27 Oct 2025): The Commonwealth has ruled out a new TDM exception for AI training at this time and instead is exploring reforms that ensure fair compensation and stronger protections for Australian creatives. The Copyright and AI Reference Group (CAIRG) continues to advise, with transparency and compensation high on the agenda.

-

The alternative that was floated: In August, the Productivity Commission suggested consulting on a TDM exception to facilitate AI. That proposal drew a rapid backlash from creators, who argued it would amount to uncompensated mass copying.

-

The direction of travel: With an exception off the table, the policy energy now shifts to licensing — how to enable AI while paying creators and bringing sunlight to training data.

Australia already knows how to do “copy first, pay fairly”

We are not starting from scratch. Australia’s Copyright Act has long used compulsory (statutory) licences to reconcile mass, socially valuable uses with fair payment:

-

Education: Part VB/related schemes allow teachers to copy and share text and images for students, in return for licence fees distributed to rightsholders.

-

Broadcast content for education & government: Screenrights administers statutory licences for copying and communicating broadcast TV/radio content by educators and government agencies, with royalties paid out to rightsholders.

These schemes prove a simple point: when individual permissions are unfeasible at scale, mandatory licensing with collective administration can align public interest and creator remuneration.

A mandatory licence for AI training: the core design

Scope

The scope of a mandatory licence regime would need to cover the reproduction and ingestion of copyright works for the purpose of training AI models (foundation and domain-specific).

To ensure it doesn’t go too far, it would need to exclude public distribution of training copies. Output uses would remain governed by ordinary copyright (no licence for output infringement, style-cloning or substitutional uses).

Ideally, the licence would cover all works protected under the Copyright Act 1968 (literary, artistic, musical, dramatic, films, sound recordings, broadcasts), whether online or offline, Australian or foreign (subject to reciprocity).

Mandatory

The licence would be mandatory for any developer (or deployer) who assembles or fine-tunes models using copies of protected works (including via third-party dataset providers).

Absent a specific free-to-use status (e.g. CC-BY with TDM permission or public domain), all AI training using covered works would require a licence and reporting.

Transparency/Reporting

Licensees would be required to maintain auditable logs identifying sources used (dataset manifests, crawling domains, repositories, catalogues).

They would also be required to provide regular transparency reports to the regulator and collecting society, with confidential treatment for genuinely sensitive items (trade secrets protected but not a shield for non-compliance). CAIRG has already identified copyright-related AI transparency as a live issue—this would operationalise it.

Register

A register of creators/rightsholders would be established with the designated collecting society (or societies) to receive distributions.

All unclaimed funds would be held and later distributed via usage-based allocation rules (with rolling claims windows), mirroring existing statutory practice in education/broadcast licences.

Rates

Setting rates and allocating royalties would be a little more complex. One way to do that would be to blend:

-

Source-side weighting (how much of each catalogue was ingested, adjusted for “substantial part” analysis); and

-

Impact-side proxies (e.g. similarity retrieval hits during training/validation; reference counts in tokenizer vocabularies; contribution metrics from dataset cards).

Rates could be set by Copyright Tribunal-style determination or by periodic ministerial instrument following public consultation.

Opt out/in

In this proposal, there would be an opt-out process with all works covered by default on a “copy first, pay fairly” basis – which would replicate current education/broadcast models and avoid a data-black-market.

Into that could be layered an opt-out right for rightsholders who object on principle (with enforceable dataset deletion duties).

An added twist could be the inclusion of opt-in premium tiers, where, for example, native-format corpora or pre-cleared archives would be priced above the baseline.

Small model & research safe harbours

A de minimis / research tier for non-commercial, low-scale research could be applied with strict size and access limits (registered institutions; no commercial deployment) to keep universities innovating without trampling rights.

Enforcement

Civil penalties could be issued for unlicensed training; aggravated penalties for concealment or falsified dataset reporting.

The regulator/collecting society could also be given audit powers , with privacy and trade-secret safeguards.

Governance: who would run it?

Australia already has experienced collecting societies and government infrastructure:

-

Text/image sector: Copyright Agency (education/government experience, distribution pipelines).

-

Screen & broadcast: Screenrights (large-scale repertoire matching, competing claims processes).

-

Music (for audio datasets): APRA AMCOS/PPCA (licensing, cue sheets, ISRC/ISWC metadata).

The Government could designate a lead collecting society per repertoire (text/image; audio; AV) under ministerial declaration, with a single one-stop portal to keep compliance simple.

Why this beats both extremes

Versus a TDM exception (now rejected):

-

Ensures real money to creators, not just “innovation” externalities.

-

Reduces litigation risk for AI companies by replacing guesswork about “fair dealing/fair use” with clear rules and receipts.

Versus a pure consent-only world:

-

Avoids impossible transaction costs of millions of one-off permissions.

-

Preserves competition by allowing local model builders to license at predictable rates instead of being locked out by big-tech private deals.

Practical details to get right (and how to solve them)

-

Identifiability of works inside massive corpora

-

Require dataset manifests and hashed URL lists on ingestion; favour sources with reliable identifiers (ISBN/ISSN/DOI/ISRC/ISWC).

-

Permit statistical allocation where atom-level matching is infeasible, backed by audits.

-

-

Outputs vs training copies

-

This licence covers training copies only. Output-side infringement, passing-off, and “style cloning” remain governed by ordinary law (and other reforms). Government focus on broader AI guardrails continues in parallel.

-

-

Competition & concentration

-

Prevent “most favoured nation” clauses and ensure FRAND-like access to the scheme so smaller labs can participate.

-

-

Privacy & sensitive data

-

Exclude personal information categories by default; align with privacy reforms and sectoral data controls.

-

-

Cross-border reciprocity

-

Pay foreign rightsholders via society-to-society deals; receive for Australians used overseas, following established collecting society practice.

-

How this could be enacted fast

-

Amend the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) to insert a new Part establishing an AI Training Statutory Licence, with regulation-making power for:

-

eligible uses;

-

reporting and audit;

-

tariff-setting criteria;

-

distribution rules and claims periods;

-

penalties and injunctions for non-compliance.

-

-

Designate collecting societies by legislative instrument.

-

Set up a portal with standard dataset disclosure templates and quarterly reporting.

-

Transitional window (e.g., 9–12 months) to allow existing models to come into compliance (including back-payment or corpus curation).

What this could mean for your organisation (now)

-

AI developers & adopters: Start curating dataset manifests and chain-of-licence documentation. If your vendors can’t or won’t identify sources, treat that as a red flag.

-

Publishers, labels, studios, creators: Register and prepare your repertoire metadata so you’re discoverable on day one. Your leverage improves if you can prove usage and ownership.

-

Boards & GCs: Build AI IP risk registers that assume licensing is coming, not that training will be exempt. The government’s latest signals align with this.

Bottom line

Australia has rejected the “train now, pay never” pathway. The cleanest middle ground is not a loophole, but a licence with teeth: mandatory participation for AI trainers, serious transparency, and fair money to the people whose works are powering the models.

We already run national-scale licences for education and broadcast. We can do it again for AI—faster than you think, and fairer than the alternatives.

The Federal Court has handed down its first civil penalty judgment under the Online Safety Act 2021 (Cth), in eSafety Commissioner v Rotondo (No 4) [2025] FCA 1191.

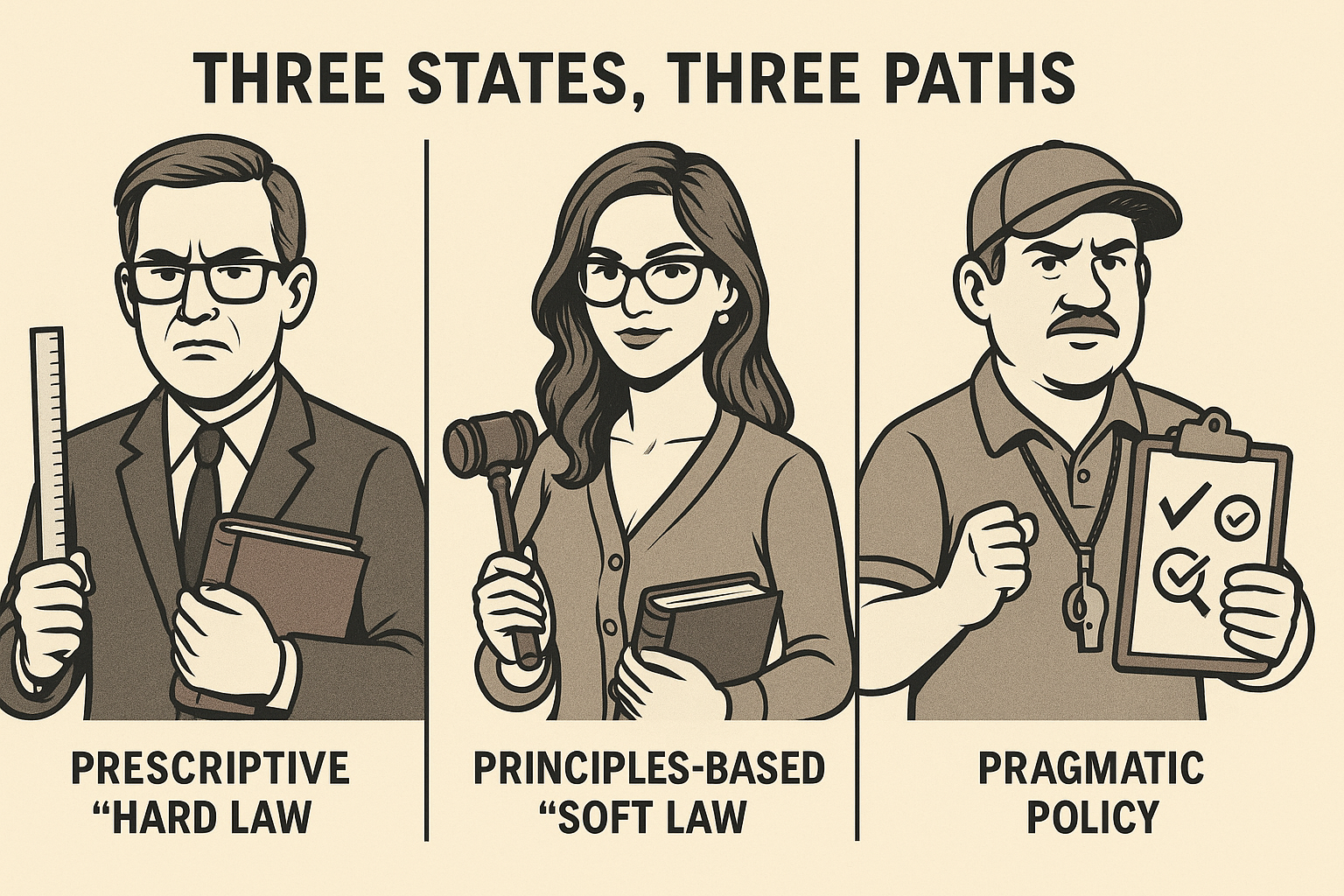

The Federal Court has handed down its first civil penalty judgment under the Online Safety Act 2021 (Cth), in eSafety Commissioner v Rotondo (No 4) [2025] FCA 1191. Australia’s courts are no longer sitting on the sidelines of the AI debate. Within just a few months of each other, the Supreme Courts of New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland have each published their own rules or guidance on how litigants may (and may not) use generative AI.

Australia’s courts are no longer sitting on the sidelines of the AI debate. Within just a few months of each other, the Supreme Courts of New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland have each published their own rules or guidance on how litigants may (and may not) use generative AI. From ChatGPT hallucinations to deepfakes in affidavits, Queensland’s courts have drawn a line in the sand.

From ChatGPT hallucinations to deepfakes in affidavits, Queensland’s courts have drawn a line in the sand.  As AI capabilities become standard fare in SaaS platforms, software providers are racing to retrofit intelligence into their offerings. But if your platform dreams of becoming the next ChatXYZ, you may need to look not to your engineering team, but to your legal one.

As AI capabilities become standard fare in SaaS platforms, software providers are racing to retrofit intelligence into their offerings. But if your platform dreams of becoming the next ChatXYZ, you may need to look not to your engineering team, but to your legal one.