AI-Generated Works & Australian Copyright — What IP Owners Need to Know

Artificial intelligence isn’t just a tool anymore — it’s a collaborator, a co-author, a designer, a composer, and sometimes, a headache. As generative AI models keep reshaping creative industries, the question for lawyers, founders, and creators is simple: Who owns what when AI helps create it?

The Australian Position: Still (Mostly) Human

Under Australian copyright law, protection only arises for an “original work” that has a human author. Section 32 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) still assumes that authorship is a human act — one involving independent intellectual effort and sufficient human skill and judgment.

That means:

-

If an AI system generates a work entirely on its own, it’s not a “work” under the Act.

-

If a human uses AI as a creative aid, and the human’s contribution involves real creative choice — not just typing a prompt — the resulting work may be protected.

-

But if the human’s input is minimal or mechanical, protection is shaky at best.

There have been plenty of official hints that legislative reform is coming, but for now, the position is clear: no human, no copyright.

Human + AI: Collaboration or Confusion?

In practice, most creative or technical outputs sit in a grey zone between human authorship and full automation.

Take these examples:

-

A marketing team uses Midjourney to create a logo based on multiple prompts and manual refinements.

-

A software developer uses GitHub Copilot to generate snippets, then curates and rewrites them.

-

A songwriter uses Suno or Udio to generate backing tracks, then layers vocals and structure.

In each case, the key question is: how much creative control did the human exert? Ownership (and enforceability) often depends less on the tool, and more on the human story behind the output.

Overseas Comparisons: Diverging Paths

-

United States: The U.S. Copyright Office has refused registration for purely AI-generated works (Thaler v Perlmutter), but allows copyright in human-authored parts of mixed works.

-

United Kingdom: Section 9(3) of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 nominally attributes authorship to “the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken” — a possible (though untested) foothold for AI users.

-

Europe: The EU’s AI Act (Artificial Intelligence Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689)) leans heavily toward transparency and data-source disclosure, rather than redefining authorship.

-

China and Japan: Both have started to recognise limited copyright protection for AI-assisted works where human creativity remains substantial.

Australia hasn’t chosen a path yet — but in my view, any eventual reform is likely to echo the UK or EU models rather than the U.S. approach.

What IP Owners Should Do Now

Until the law catches up, contractual clarity is your best protection.

-

Define ownership up-front: Ensure contracts, employment agreements, and service terms specify who owns outputs “created with the assistance of AI tools.” Clauses that tie ownership to “human input” and “creative control” can avoid later disputes.

-

Track human contribution: Keep records of prompts, edits, decisions, and drafts — proof of human creativity can become decisive evidence if ownership is challenged.

-

Check your inputs: Many AI systems are trained on datasets containing copyrighted material. Using their outputs commercially could expose you to infringement risk if the output is too close to the training data.

-

Disclose AI use where relevant: For regulators (and some clients), transparency is now part of “reasonable steps” under APP 11 of the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) and emerging AI-governance frameworks.

-

Consider alternative protection: Where copyright may fail, consider trade marks, registered designs, or even confidential-information regimes for valuable AI-assisted outputs.

The Next Frontier: Authorship by Prompt?

The next legal battleground may well be prompt authorship — whether the person crafting complex or structured prompts can claim copyright in the resulting output or in the prompt itself. Early commentary suggests yes, if the prompt reflects creative skill and judgment, but this remains untested in Australian courts.

Final Thoughts …

AI isn’t erasing copyright — it’s forcing it to evolve. For now, the safest position is that human-directed, human-shaped works remain protectable. Purely machine-generated ones don’t.

But the creative frontier is moving fast, and so is the legal one. If you’re commissioning, creating, or commercialising AI-generated content, assume that ownership must be earned through human input — and documented accordingly.

Australia’s copyright and privacy frameworks are both in flux. Expect further reform by mid-2026, when the government’s broader AI and IP Reform Roadmap is due.

Until then: contract it, track it, and own it.

When 86 gigabytes of patient data — including health, financial and identity information — hit the dark web after a ransomware attack, the fallout was always going to be brutal.

When 86 gigabytes of patient data — including health, financial and identity information — hit the dark web after a ransomware attack, the fallout was always going to be brutal.

The Federal Court has handed down its first civil penalty judgment under the Online Safety Act 2021 (Cth), in eSafety Commissioner v Rotondo (No 4) [2025] FCA 1191.

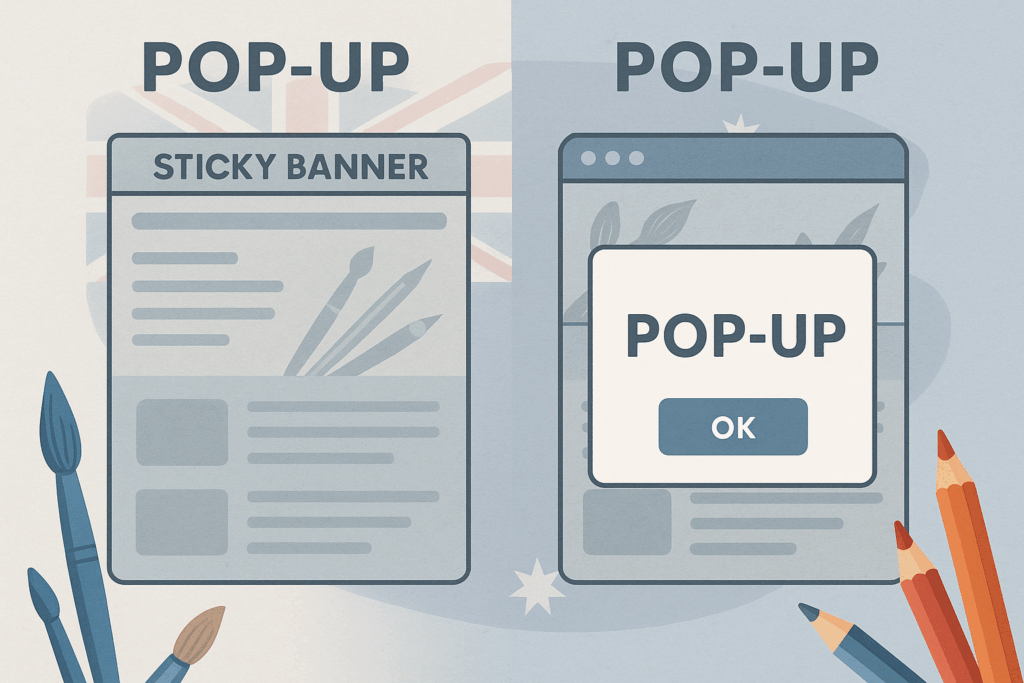

The Federal Court has handed down its first civil penalty judgment under the Online Safety Act 2021 (Cth), in eSafety Commissioner v Rotondo (No 4) [2025] FCA 1191. When two businesses with nearly identical names lock horns, things usually come down to trade marks, passing off, and reputation. But in Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd v Jackson’s Art Supplies Ltd (No 2) [2025] FCA 1127, the real fight was over disclaimers, pop-ups, sticky banners, and user attention spans.

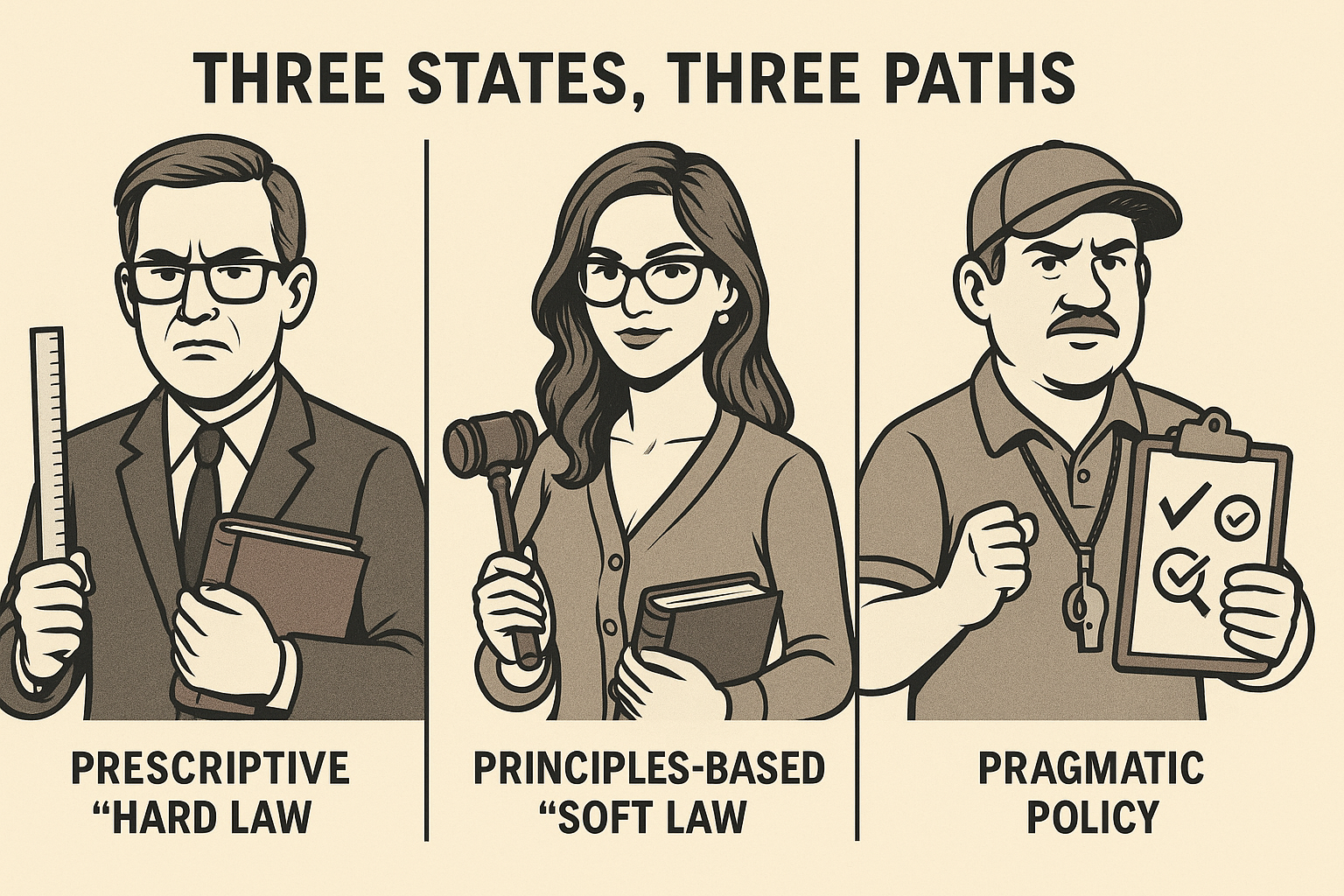

When two businesses with nearly identical names lock horns, things usually come down to trade marks, passing off, and reputation. But in Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd v Jackson’s Art Supplies Ltd (No 2) [2025] FCA 1127, the real fight was over disclaimers, pop-ups, sticky banners, and user attention spans. Australia’s courts are no longer sitting on the sidelines of the AI debate. Within just a few months of each other, the Supreme Courts of New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland have each published their own rules or guidance on how litigants may (and may not) use generative AI.

Australia’s courts are no longer sitting on the sidelines of the AI debate. Within just a few months of each other, the Supreme Courts of New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland have each published their own rules or guidance on how litigants may (and may not) use generative AI.