From ChatGPT hallucinations to deepfakes in affidavits, Queensland’s courts have drawn a line in the sand.

From ChatGPT hallucinations to deepfakes in affidavits, Queensland’s courts have drawn a line in the sand.

Two new guidelines, released on 15 September 2025, map out how judges and court users should (and shouldn’t) use AI in litigation.

Two Audiences, One Big Message

Queensland is the latest Australian jurisdiction to publish formal, court-wide rules for generative AI – and it hasn’t stopped at one audience.

-

Judicial Officers: The first guideline is aimed at judges and tribunal members. It stresses confidentiality, accuracy, and ethical responsibility, and makes clear that AI must never be used to prepare or decide judgments.

-

Non-Lawyers: The second is written in plain English for self-represented litigants, McKenzie friends, lay advocates and employment advocates. It’s blunt: AI is not a substitute for a qualified lawyer.

Together, they show the courts know AI isn’t a future problem — it’s already walking into the courtroom (and it’s not hiding under the desk).

What the Courts Are Worried About

The guidelines read like a checklist of every AI-related nightmare scenario:

-

Hallucinations: Fabricated cases, fake citations, and quotes that don’t exist.

-

Confidentiality breaches: Entering suppressed or private information into a chatbot could make it “public to all the world”.

-

Copyright and plagiarism: Summarising textbooks or IP materials via AI may breach copyright.

-

Misleading affidavits: Self-reps relying on AI risk filing persuasive-looking documents that contain substantive errors.

-

Deepfakes: Courts warn of AI-generated forgeries in text, images and video.

The judicial guideline even suggests judges may need to ask outright if AI has been used when dodgy submissions appear — especially if the citations “don’t sound familiar”.

Consequences for Misuse

The courts aren’t treating this as academic theory. Practical consequences are built in:

-

Costs orders: Non-lawyers who waste court time by filing AI-generated fakes could be hit with costs.

-

Judicial oversight: Judges may require lawyers to confirm that AI-assisted research has been independently verified.

-

Expert reports: Experts may be asked to disclose the precise way they used AI in forming an opinion.

That’s real accountability — not just “guidance”.

Why IP Lawyers Should Care

For IP practitioners, one section stands out: the copyright and plagiarism warnings. Both sets of guidelines caution that using AI to re-package copyrighted works can infringe rights if the summary or reformulation substitutes for the original.

This matters for more than pleadings. It cuts across creative industries, publishing, and expert evidence. Expect to see copyright creeping into arguments about how AI-assisted evidence is prepared and presented.

The Bigger Picture

Queensland now joins Victoria and NSW in representing Australia’s formal approach to use of AI in the courtroom. Courts in the US, UK and Canada have already started issuing AI guidance. Australia now joins the global conversation on how to balance innovation, access to justice, and the integrity of the judicial process.

For lawyers, the message is simple: use AI carefully, verify everything, and never outsource your professional responsibility. For litigants in person, the message is even simpler: AI is not your lawyer.

IP Mojo Takeaway

Queensland’s twin AI guidelines are a watershed moment. They bring generative AI out of the shadows and into the courtroom spotlight.

And whether you’re a judge, a barrister, or a self-rep with a smartphone, the new rules are clear: if you use AI in court, you own the risks.

At the time of publishing this post, you can find the guidelines here and here.

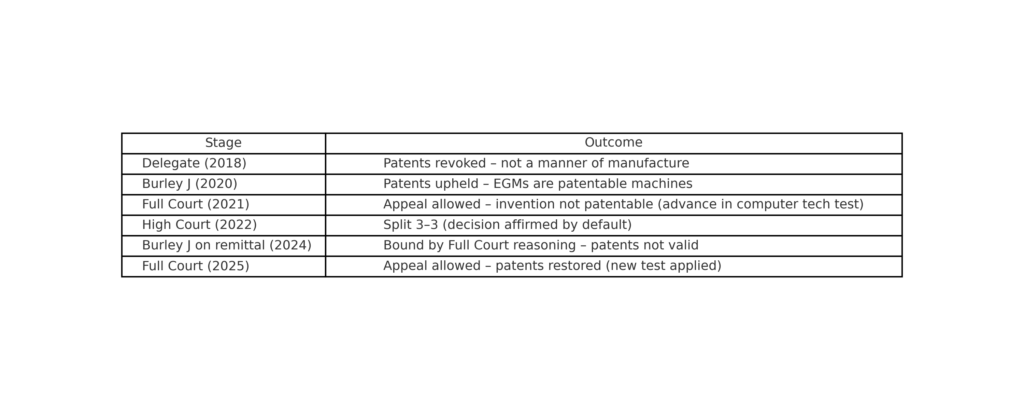

When does a slot machine cross the line from an abstract idea to a patentable invention?

When does a slot machine cross the line from an abstract idea to a patentable invention?  Cue the latest appeal.

Cue the latest appeal. When Epic Games went head-to-head with Apple, the Federal Court found that Apple misused its market power by locking iOS developers into the App Store and its payment system. That was big. But the Anthony v Apple class action takes it a step further: what if Apple has been overcharging Australian developers and consumers for years?

When Epic Games went head-to-head with Apple, the Federal Court found that Apple misused its market power by locking iOS developers into the App Store and its payment system. That was big. But the Anthony v Apple class action takes it a step further: what if Apple has been overcharging Australian developers and consumers for years? When Epic Games took on Apple in the US and Europe, the headlines practically wrote themselves – it was billed as a David-and-Goliath showdown between the Fortnite maker and the Cupertino colossus. Now, the same fight has reached Australian shores — and the Federal Court has bitten into Apple’s walled garden.

When Epic Games took on Apple in the US and Europe, the headlines practically wrote themselves – it was billed as a David-and-Goliath showdown between the Fortnite maker and the Cupertino colossus. Now, the same fight has reached Australian shores — and the Federal Court has bitten into Apple’s walled garden. As AI capabilities become standard fare in SaaS platforms, software providers are racing to retrofit intelligence into their offerings. But if your platform dreams of becoming the next ChatXYZ, you may need to look not to your engineering team, but to your legal one.

As AI capabilities become standard fare in SaaS platforms, software providers are racing to retrofit intelligence into their offerings. But if your platform dreams of becoming the next ChatXYZ, you may need to look not to your engineering team, but to your legal one. Imagine this: you take a screenshot of your favourite SaaS dashboard, upload it to a no-code AI tool, and minutes later you have a functioning version of the same interface — layout, buttons, styling, maybe even a working backend prototype. Magic? Almost.

Imagine this: you take a screenshot of your favourite SaaS dashboard, upload it to a no-code AI tool, and minutes later you have a functioning version of the same interface — layout, buttons, styling, maybe even a working backend prototype. Magic? Almost.