IMDb v DMDb: One Letter’s Difference Not Enough

Zumedia Inc’s attempt to register DMDb as a trade mark in Australia fell flat—thanks to its awkward proximity to a far more famous acronym: IMDb.

Zumedia, a Canadian company behind a digital media platform called “Digital Media Database,” applied to extend its international trade mark registration for DMDb into Australia. But IMDb, the internet’s go-to entertainment database, wasn’t about to let that slide. Backed by nearly 30 years of global use and widespread recognition in Australia, IMDb opposed the extension under section 60 of the Trade Marks Act 1995.

IP Australia sided with IMDb. Despite the difference in the first letter, Delegate Tracey Berger found the marks visually and aurally similar, especially given the overlapping services—both related to searchable databases of entertainment content. Australian users, she held, could easily assume DMDb was affiliated with or endorsed by IMDb.

Zumedia tried to argue that DMDb was a unique acronym and that “Db” simply stood for “database.” Ironically, that only strengthened the opposition’s case: as the Delegate pointed out, consumers often remember brands imperfectly. The shared “-MDb” element was enough to trigger a mistaken belief in a connection.

She also referenced prior cases—including AAMI and Tivo v Vivo—to reinforce the point: when a well-known mark has a strong reputation in the same field, even small differences won’t eliminate the risk of confusion.

The outcome? Extension of protection refused. Costs awarded against Zumedia.

🎬 IP Mojo Takeaway: If your brand sits one letter away from an iconic name in the same industry, don’t count on slipping through. Trade mark law doesn’t look kindly on near-misses that come too close to the main act.

You’ve found the perfect brand name. It’s clever. Catchy. The domain is available. The branding agency loves it. You’re ready to roll.

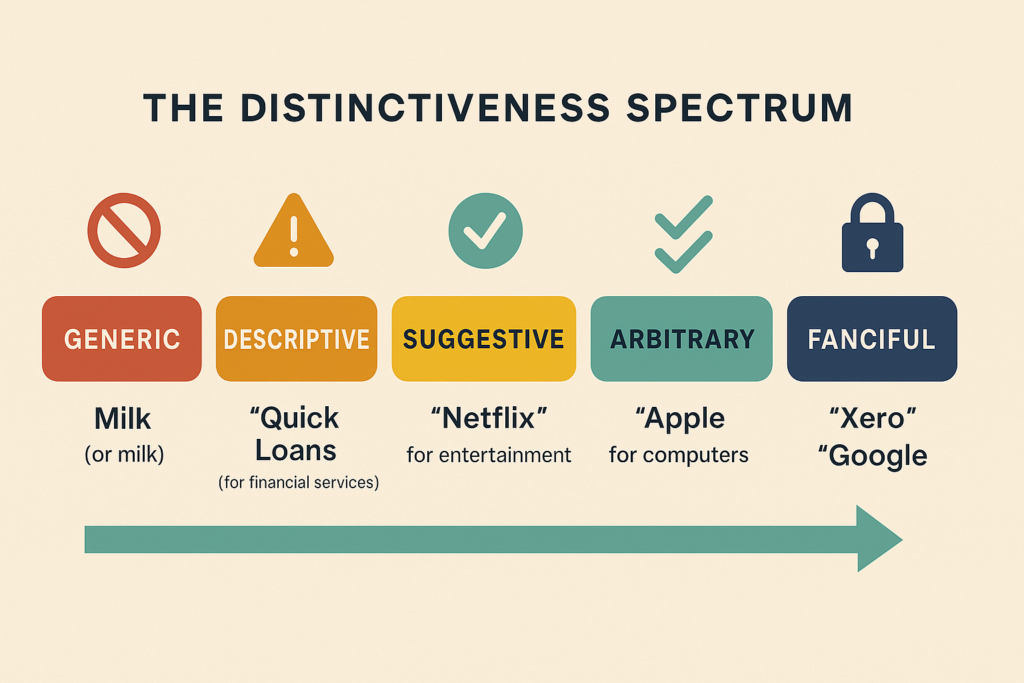

You’ve found the perfect brand name. It’s clever. Catchy. The domain is available. The branding agency loves it. You’re ready to roll. Not every brand name is created equal. In the eyes of the law, the more descriptive your mark, the weaker your rights.

Not every brand name is created equal. In the eyes of the law, the more descriptive your mark, the weaker your rights. The long-running IP clash between Australian designer Katie Taylor (aka Katie Perry) and US popstar Katheryn Hudson (aka Katy Perry) has now reached the High Court. Both sides have filed their submissions—and the gloves are well and truly off.

The long-running IP clash between Australian designer Katie Taylor (aka Katie Perry) and US popstar Katheryn Hudson (aka Katy Perry) has now reached the High Court. Both sides have filed their submissions—and the gloves are well and truly off. When most people talk about a “brand”, they’re really thinking about a vibe: a gut-level feel, a cultural footprint, an aesthetic. And all of that matters — but from a legal perspective, a brand only really lives and breathes through what you can protect.

When most people talk about a “brand”, they’re really thinking about a vibe: a gut-level feel, a cultural footprint, an aesthetic. And all of that matters — but from a legal perspective, a brand only really lives and breathes through what you can protect. In the world of IP, form usually follows function—until it tries to live forever.

In the world of IP, form usually follows function—until it tries to live forever. The Case in Brief

The Case in Brief