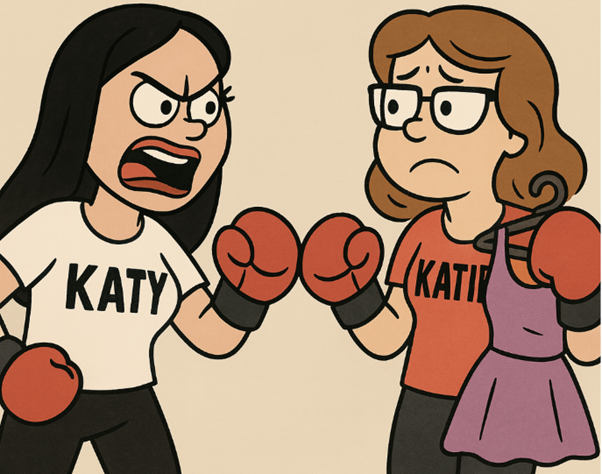

Perry v Perry – Round 3 in the High Court

The long-running IP clash between Australian designer Katie Taylor (aka Katie Perry) and US popstar Katheryn Hudson (aka Katy Perry) has now reached the High Court. Both sides have filed their submissions—and the gloves are well and truly off.

The long-running IP clash between Australian designer Katie Taylor (aka Katie Perry) and US popstar Katheryn Hudson (aka Katy Perry) has now reached the High Court. Both sides have filed their submissions—and the gloves are well and truly off.

Let’s unpack the arguments.

🎤 The Trade Mark at War

At the heart of the dispute is Taylor’s registered mark KATIE PERRY for clothing, registered in 2009. Hudson’s team argues that it should never have been allowed to stay on the register—because of her own fame under the name Katy Perry, and the likelihood of confusion in the public mind.

This fight has already been through:

-

The Federal Court (where Taylor won on infringement, but the respondents failed to cancel her trade mark),

-

and the Full Federal Court (which overturned the trial judge and ordered cancellation under ss 60 and 88(2)(c)).

Now, Taylor’s appeal to the High Court gives us an opportunity to see how the highest court will treat the tricky interplay between reputation, confusion, and celebrity brand extension.

⚖️ Key Appeal Issues

The submissions squarely raise three points of trade mark law importance:

-

Reputation Must Be in a Trade Mark, Not Just a Name

Taylor argues (citing Self Care IP) that reputation in a person isn’t enough—section 60 requires a reputation in a trade mark used to distinguish goods or services. The respondents say that “Katy Perry” was functioning as a mark in connection with music and entertainment—even if not for clothes—by the priority date. -

Deceptive Similarity ≠ Confusion from Reputation

Taylor says the Full Court wrongly blurred section 60 with the s 10 concept of deceptive similarity, using “imperfect recollection” logic that belongs elsewhere. She maintains that just because the names look similar doesn’t mean there’s a s 60 ground for cancellation unless confusion arises because of the earlier mark’s reputation. -

Discretion Under s 89: Who’s at Fault?

The Full Court held that Taylor’s act of applying for the mark—with knowledge of Katy Perry’s fame—was enough to defeat the saving provision in s 89. Taylor argues this turns s 89 into a dead letter. Is the act of registration itself always a fault? If so, what’s left for discretion to do?

👑 Celebrity Brands and Trade Mark Realpolitik

The respondents press the idea that by 2008, there was an established trend of pop stars launching fashion lines—and that any member of the public hearing “KATIE PERRY” on a swing tag might assume a connection with the singer. They argue:

-

Reputation in entertainment was enough to ground confusion over clothes;

-

The law shouldn’t insist on technical “use as a trade mark” when real-world fame does the work.

Taylor says: Not so fast. Reputation should attach only to actual marks used to distinguish goods. And if the singer hadn’t sold clothes in Australia before the priority date—let alone registered a mark for clothing—why should she get a monopoly over a local designer’s name?

🧵 Threads to Watch

This appeal gives the High Court a chance to clarify several issues that matter beyond this case:

-

What counts as reputation in a “trade mark”? Is global fame enough?

-

Does fame create a shadow monopoly over unrelated goods where the celebrity hasn’t yet traded?

-

When is confusion “likely”? Must it be tied to reputation for the same goods?

-

Is s 89 still alive? Or does knowledge at the time of filing always kill it?

🪙 Final Stitch

This is a rare IP battle where both sides have established, legitimate reputations—and where delay, co-existence efforts, and evolving fame all muddy the waters. Whatever the High Court decides, it’s likely to have ripple effects across celebrity branding, merchandising strategy, and the interpretation of section 60.

🧵 Stay tuned.

In the world of entertainment, nothing stops a production faster than a copyright claim — even when the claimant doesn’t actually have a leg (or claw) to stand on.

In the world of entertainment, nothing stops a production faster than a copyright claim — even when the claimant doesn’t actually have a leg (or claw) to stand on. When most people talk about a “brand”, they’re really thinking about a vibe: a gut-level feel, a cultural footprint, an aesthetic. And all of that matters — but from a legal perspective, a brand only really lives and breathes through what you can protect.

When most people talk about a “brand”, they’re really thinking about a vibe: a gut-level feel, a cultural footprint, an aesthetic. And all of that matters — but from a legal perspective, a brand only really lives and breathes through what you can protect. In the world of IP, form usually follows function—until it tries to live forever.

In the world of IP, form usually follows function—until it tries to live forever. The Case in Brief

The Case in Brief Launching a brand? Running a business? Advising one? Then you already know the power of a strong name, logo, or tagline. But what makes a brand not just memorable — but legally defensible?

Launching a brand? Running a business? Advising one? Then you already know the power of a strong name, logo, or tagline. But what makes a brand not just memorable — but legally defensible? Firstmac’s long-running dispute with Zip Co over the word “ZIP” has taken another sharp turn—this time with Zip Co applying for special leave to appeal to the High Court.

Firstmac’s long-running dispute with Zip Co over the word “ZIP” has taken another sharp turn—this time with Zip Co applying for special leave to appeal to the High Court.