Aristocrat’s Jackpot: Full Court Revives Gaming Machine Patents

When does a slot machine cross the line from an abstract idea to a patentable invention?

When does a slot machine cross the line from an abstract idea to a patentable invention?

After years of litigation, remittals, and even a 3–3 deadlock in the High Court, the Full Federal Court has finally tipped the balance in Aristocrat’s favour.

🎰 The Long Spin

Aristocrat has been fighting since 2018 to keep its patents over electronic gaming machines (EGMs) with “configurable symbols” — feature games that change play dynamics and prize allocation. The Commissioner argued these were just abstract rules of a game dressed up in software. Aristocrat said they were genuine machines of a particular construction that yielded a new and useful result.

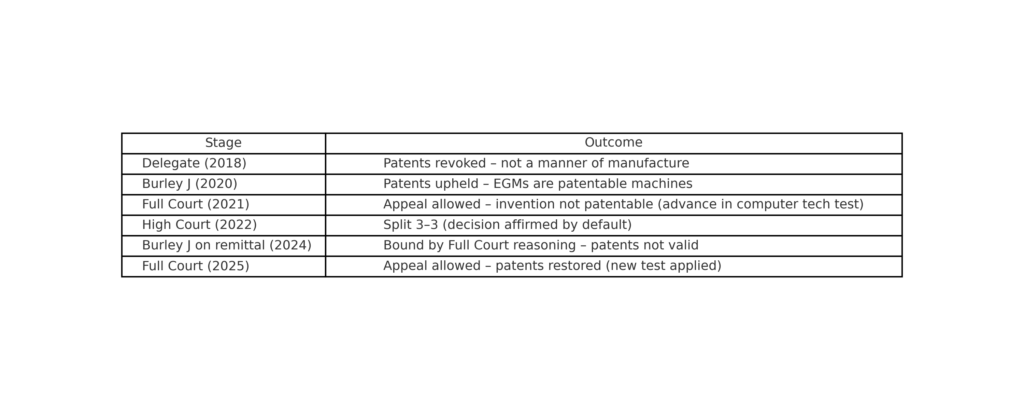

The case bounced through:

-

Delegate (2018): patents revoked.

-

Burley J (2020): Aristocrat wins.

-

Full Court (2021): Aristocrat loses (majority invents “advance in computer technology” test).

-

High Court (2022): split 3–3, affirming the Full Court’s result by default under Judiciary Act s 23(2)(a).

-

Remittal (2024): Burley J reluctantly applies Full Court reasoning against Aristocrat.

Cue the latest appeal.

Cue the latest appeal.

⚖️ The Precedent Puzzle

The Full Court (Beach, Rofe & Jackman JJ) confronted a thorny problem: should it stick to its own 2021 reasoning when the High Court had unanimously rejected that reasoning, even though no majority emerged?

The answer: No.

-

Only majority or unanimous High Court views are binding.

-

But the High Court’s unanimous criticism provided a “compelling reason” to abandon the earlier Full Court approach.

-

The Court found “constructive error” — not blaming Burley J, but recognising the law had to move on.

🖥️ Rethinking “Manner of Manufacture”

The Court reframed the test for computer-implemented inventions:

-

Not patentable: an abstract idea manipulated on a computer.

-

Patentable: an abstract idea implemented on a computer in a way that creates an artificial state of affairs and useful result.

Applying this, Aristocrat’s claim 1 was patentable — and by extension, so were the dependent claims across its four patents. The EGMs weren’t just abstract gaming rules. They were machines, purpose-built to operate in a particular way.

💡 Why It Matters

-

For patentees: This revives hope for computer-implemented inventions beyond “pure software” where technical implementation creates a new device or process.

-

For examiners: IP Australia may need to recalibrate examination practice on software-related patents — the “advance in computer technology” yardstick is gone.

-

For practitioners: This is a case study in how precedent, process, and patents collide. The High Court’s split didn’t end the story — it forced the Full Court to resolve it.

🚀 Takeaway

The Full Court has effectively reset the slot reels. Aristocrat’s EGMs are back in play, and the scope of patentable computer-implemented inventions in Australia looks a little brighter.

Sometimes the house doesn’t win.

The most dangerous thing about copyright? What people think they know.

The most dangerous thing about copyright? What people think they know. Copyright doesn’t stop at the border. Thanks to international treaties, Australian works enjoy protection in most countries around the world.

Copyright doesn’t stop at the border. Thanks to international treaties, Australian works enjoy protection in most countries around the world. What happens when copyright infringement is admitted but the “big ticket” remedies fall away?

What happens when copyright infringement is admitted but the “big ticket” remedies fall away? Copyright gives creators powerful rights. But those rights only matter if you can enforce them when someone crosses the line.

Copyright gives creators powerful rights. But those rights only matter if you can enforce them when someone crosses the line. If your brand is built on praise, don’t be surprised when you can’t block others from using it.

If your brand is built on praise, don’t be surprised when you can’t block others from using it.