Menus Won’t Save You: Merivale’s “est” Loses Class 16 in Non-Use Battle

When your brand is famous in one field, can it keep rights in goods you barely touch?

When your brand is famous in one field, can it keep rights in goods you barely touch?

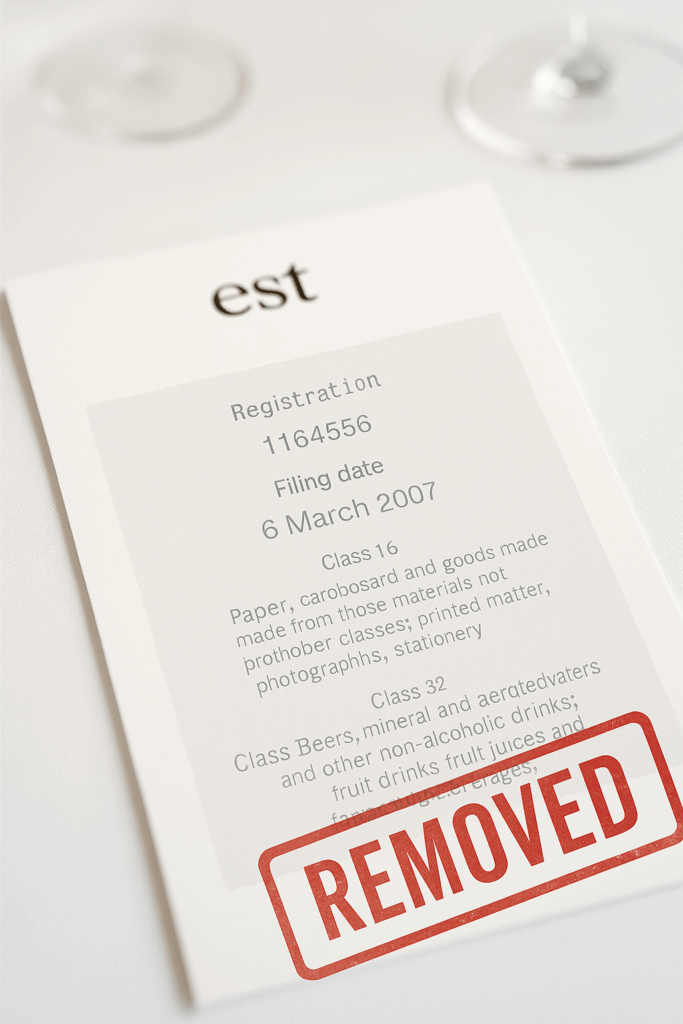

Merivale’s long-closed Sydney fine-dining institution est recently learned the hard way that incidental printed materials — like menus or event stationery — won’t necessarily save a trade mark registration for “printed matter” in Class 16.

The Players

-

Hemmes Trading Pty Ltd (Merivale) – Owner of the est restaurant brand since 2000.

-

Est Living Pty Ltd – A design publisher with an online magazine “Est” since 2011.

Est Living applied under s 92(4)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) to partially remove Merivale’s est registration for non-use in Class 16 (paper goods, printed matter, photographs, stationery).

The Evidence Game

Merivale’s “use” case relied on:

-

Wedding/event menus branded est

-

Mentions of est in Merivale’s “Weddings” book and on social media

-

Contracts and invitations naming est as a venue

-

An argument that menus were “goods in the course of trade” like in the Realtor decision

The problem?

The Delegate found:

-

Menus and invitations were ancillary to restaurant services — not sold or traded as Class 16 goods.

-

Branding on venue/event collateral was dominated by “Merivale”, with est appearing only as a location reference.

-

No convincing evidence of est-branded printed goods in the Relevant Period that actually functioned as a trade mark for Class 16 goods.

The “COVID Obstacle” Argument

Merivale claimed pandemic lockdowns were an “obstacle to use” under s 100(3)(c). The Delegate wasn’t persuaded:

-

The restaurant closed for renovations before COVID.

-

Private events still ran during the period, so use was possible.

-

Delay in reopening wasn’t justified by pandemic impacts alone.

Discretion? Declined.

The Registrar’s discretion under s 101(3) is a safety valve, but it’s not there to protect unused marks for sentimental reasons. Public interest tipped the scales:

-

est had a dining reputation, but not for Class 16 goods.

-

Keeping unused goods on the Register would “clog” the system and create unnecessary hazards for other traders.

The Result

Partial removal succeeded. The est registration now covers only:

Class 32: Beers, mineral and aerated waters, non-alcoholic drinks, fruit drinks/juices, syrups, and preparations for making beverages.

Costs were awarded against Merivale.

IP Mojo Takeaways

-

Goods vs Services – Use for services doesn’t automatically translate to use for goods, even if the goods are part of the service experience.

-

Menus ≠ Market Goods – If they’re free, incidental, and tied to the service, they probably won’t save your Class 16 claim.

-

Obstacle Defence Is Narrow – COVID didn’t help here because the closure predated it and events continued.

-

Discretion Won’t Fill the Gaps – If you can’t prove use or genuine intent, public interest will clear the Register.

Citation: Est Living Pty Ltd v Hemmes Trading Pty Ltd [2025] ATMO 142

Owning copyright doesn’t mean you have to keep it locked away. In fact, some of the most powerful uses of copyright come from sharing it—on your terms. That’s where licensing and assignment come in.

Owning copyright doesn’t mean you have to keep it locked away. In fact, some of the most powerful uses of copyright come from sharing it—on your terms. That’s where licensing and assignment come in. The linen wars have gone all the way to the top.

The linen wars have gone all the way to the top. If it’s online, it’s free to use… right? Wrong.

If it’s online, it’s free to use… right? Wrong. When you win a trade mark infringement case, the natural instinct is to go after the other side’s profits. After all, why should the infringer keep any benefit from piggybacking off your brand? But as Kretchmer Enterprises Pty Limited v AMR Manufacturing Pty Limited [2025] FedCFamC2G 1394 shows, that’s often easier said than done.

When you win a trade mark infringement case, the natural instinct is to go after the other side’s profits. After all, why should the infringer keep any benefit from piggybacking off your brand? But as Kretchmer Enterprises Pty Limited v AMR Manufacturing Pty Limited [2025] FedCFamC2G 1394 shows, that’s often easier said than done. It was always going to be a cheeky choice — BROWN NOSE DAY for a bowel cancer fundraiser — but was it unlawfully close to RED NOSE DAY and its colourful cousins?

It was always going to be a cheeky choice — BROWN NOSE DAY for a bowel cancer fundraiser — but was it unlawfully close to RED NOSE DAY and its colourful cousins?