Copy That, Part 5 – Exceptions and Limitations: Fair Dealing in Australia

There’s a common misconception that “if I’m not making money from it, it’s fine.” Not so.

There’s a common misconception that “if I’m not making money from it, it’s fine.” Not so.

In Australia, there are only very specific circumstances where you can use someone else’s copyright material without permission—and they’re called fair dealing exceptions.

These are not catch-all “free use” rules. They’re targeted, purpose-driven carve-outs in the Copyright Act, and if you step outside them, you risk infringement.

The five main fair dealing purposes

You can use copyright material without permission if your use is fair and is for one of these legally recognised purposes:

-

Research or study

-

This includes both academic and private study.

-

Factors like the amount used and the purpose matter—copying an entire textbook probably isn’t “fair.”

-

-

Criticism or review

-

The material must genuinely be part of a critique or review, and you must provide sufficient acknowledgment of the source.

-

-

Parody or satire

-

This can be humorous or biting, but must be a genuine parody or satire—not just borrowing the work for entertainment value.

-

-

Reporting the news

-

Use must be connected to an actual news report, not just general commentary. Proper attribution is required.

-

-

Giving professional legal advice

-

Lawyers can use works as part of providing legal advice to clients.

-

The fairness test

Even if you meet one of the above purposes, your use must also be “fair.” Courts look at factors such as:

-

The purpose and character of your use

-

The nature of the work

-

The amount and substantiality of the portion used

-

Whether your use competes with or harms the market for the work

Not to be confused with US “fair use”

The US doctrine of “fair use” is broader and more flexible. Australia’s fair dealing is narrow—if your use doesn’t fit one of the listed purposes, there’s no exception, no matter how “reasonable” it seems.

IP Mojo tip: When in doubt, get permission

Fair dealing can be a powerful defence, but it’s not a free pass. If you’re outside the scope of the exceptions, or if “fairness” is debatable, permission (or a licence) is the safest route.

Next up in our Copy That series:

Part 6 – Copyright and the Digital Age: Online Use, Streaming, and AI

Because copyright law applies online too—and the rules can surprise you.

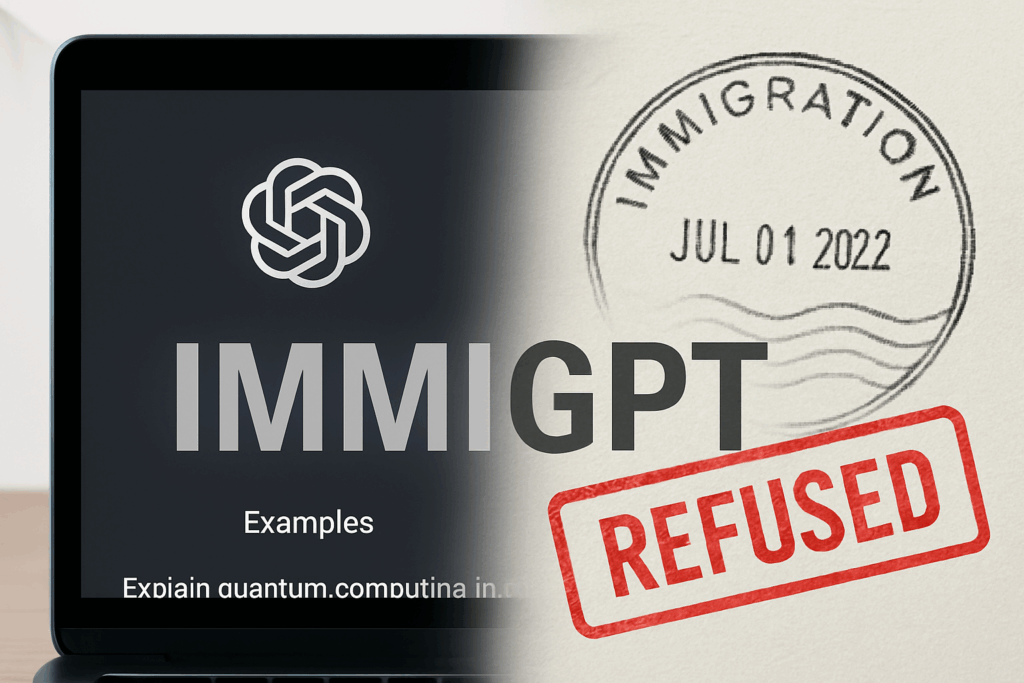

What happens when you take a world-famous tech acronym and bolt it onto your own business name?

What happens when you take a world-famous tech acronym and bolt it onto your own business name? Nothing lasts forever—not even copyright.

Nothing lasts forever—not even copyright. Copyright isn’t just about money—it’s also about dignity.

Copyright isn’t just about money—it’s also about dignity.

You wrote it. You made it. You own it… right?

You wrote it. You made it. You own it… right?