Brand Control, Bonus Part 4A: “Black, White, or Brand Colours?” — Filing Your Trade Mark in the Right Format

When it comes to registering your logo as a trade mark, most people obsess over what to file — but give little thought to how they file it.

When it comes to registering your logo as a trade mark, most people obsess over what to file — but give little thought to how they file it.

That might sound cosmetic. It’s not.

Whether you lodge your logo in colour, greyscale, or black and white can significantly affect your legal rights — especially when it comes time to enforce them or defend against a non-use challenge.

⚖️ Why Format Matters

The version of your logo that you register defines the scope of your protection. That includes not only the design itself, but also the colour (or lack of it). Get this wrong, and you may end up with a trade mark that’s narrower than you think — or worse, vulnerable to attack.

Let’s break down the key options.

🖤 Filing in Black and White (or Greyscale)

This is the default for many businesses — and with good reason.

Pros:

-

Broader protection: A black-and-white filing generally covers all colour variants, meaning you can enforce your rights even if you present the logo in red, green, blue, or rainbow.

-

Future-proofing: Gives you flexibility if your brand palette evolves.

-

Administrative simplicity: No need to worry about strict consistency between your filed version and the colours you actually use.

Cons:

-

If colour is a core brand element (think Cadbury purple or Tiffany blue), filing in black and white might dilute your distinctiveness case.

-

In the EU and some other jurisdictions, courts and registries have begun interpreting black-and-white marks more narrowly — treating them as literally black-and-white. That means that in those jurisdictions, using your mark in colour may not constitute use of your registered black-and-white version. This trend hasn’t reached Australia (yet), but it’s worth noting.

🎨 Filing in Colour

In some cases, colour isn’t just decoration — it’s branding. If your logo’s colour scheme is heavily marketed and instantly recognisable, a colour filing might be worth it.

Pros:

-

Supports claims to distinctiveness through colour — which can help if you’re pursuing colour trade mark protection in its own right.

-

Reflects real-world use if your brand always appears in that colour scheme.

Cons:

-

May limit your rights in some jurisdictions — but not in Australia, where a logo filed in colour will generally still cover variations in other colours unless colour has been expressly claimed as part of the trade mark.

-

In Australia, there’s no general risk of non-use removal for using your logo in different colours — unless your registration specifically claims colour as a feature. That said, it’s still cleaner (and less arguable) to use the mark in a form close to the one registered.

🎯 Some Things to Watch

1. Evidence of Use Needs to Align (More or Less)

If your logo is registered in colour but you only ever use it in black and white (or vice versa), and you’re defending against a non-use removal action, your evidence might still be accepted — but it’s always safer if the colours match, or if colour wasn’t part of the mark to begin with.

2. Madrid Protocol and International Filings May Be Affected

Whichever registration forms your Madrid Protocol base — whether or not it’s an Australian application — the representation you file (including colours) will carry through to your international applications.

Some jurisdictions treat colour as limiting, even if Australia doesn’t. In the EU, China, South Korea and others, colour is more tightly tied to the rights you’re granted. So what might be broad in Australia could be narrow overseas if you rely on a colour version as your base.

🧭 Rule of thumb: File in each jurisdiction — including separately if necessary — in the same format in which you propose to use the mark there.

3. Misalignment with Brand Identity

If your brand identity is highly colour-driven (again, Cadbury purple or Tiffany blue), filing a version in colour without claiming the colour might undercut future arguments that the colour is distinctive.

You can’t have it both ways: either colour matters, or it doesn’t. If it does, claim it. If it doesn’t, don’t build your distinctiveness case on it later.

✅ Best Practice in Australia

So, what should you do?

-

If colour isn’t essential to your brand’s identity: stick with black and white (or greyscale) for broader and more adaptable coverage — unless you’re filing via the Madrid Protocol and plan to use the mark in colour in a colour-sensitive jurisdiction. In that case, you may need to file your base application in colour too — as long as that won’t cause issues in your base jurisdiction.

-

If colour is central to your brand strategy: consider filing both a colour version and a black-and-white version — or prepare strong use evidence to back your colour claim.

-

If your logo use varies across products or channels: a black-and-white filing gives you the most legal breathing room in Australia. Or, if your variants differ materially, file multiple versions (or a series application, where appropriate).

⚠️ Filing in multiple formats may mean more upfront cost — but it could save you a fortune later if your brand is challenged or infringed.

💡 IP Mojo Tip

Don’t confuse design preference with legal strategy. Your brand might look best in colour — but from a legal perspective, black and white may give you more options.

That said, the best general rule is this: File it how you propose to use it.

If you know the colour combinations you plan to use for the medium term, consider a series application covering those variants — or file multiple applications if that’s cleaner for your international strategy.

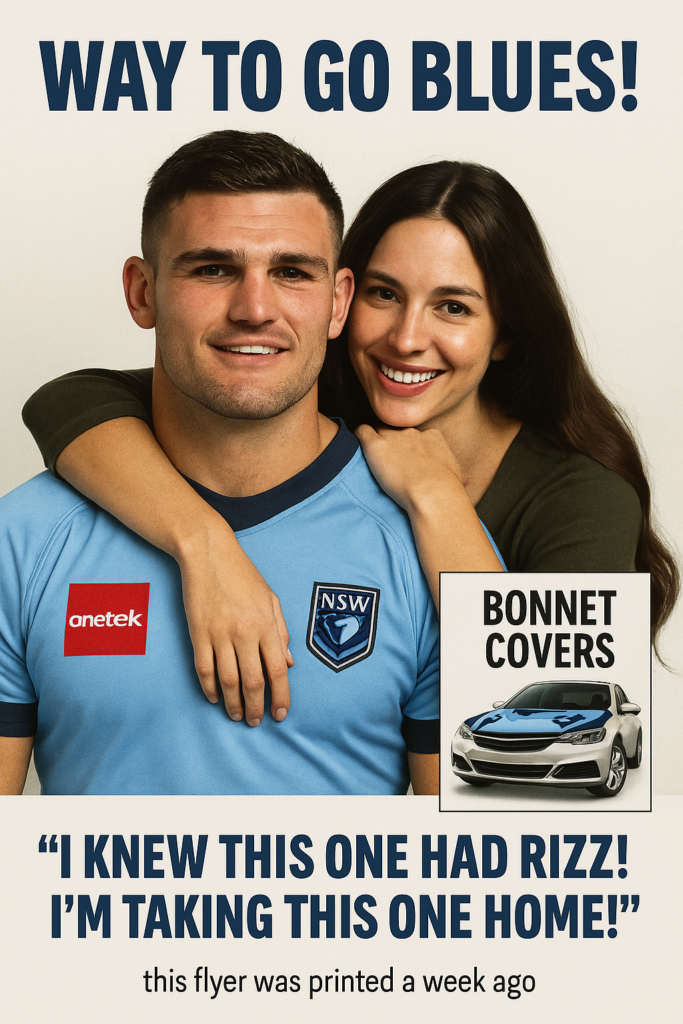

Rugby league star Nathan Cleary is the latest Australian celebrity to have his image hijacked for commercial gain without consent — a reminder that in the AI age, the unauthorised use of someone’s likeness isn’t just a reputational risk. It’s often unlawful, and sometimes even criminal.

Rugby league star Nathan Cleary is the latest Australian celebrity to have his image hijacked for commercial gain without consent — a reminder that in the AI age, the unauthorised use of someone’s likeness isn’t just a reputational risk. It’s often unlawful, and sometimes even criminal. You’ve chosen your name. You’ve cleared it. You’re confident it’s distinctive and available. Now it’s time to make it yours — legally.

You’ve chosen your name. You’ve cleared it. You’re confident it’s distinctive and available. Now it’s time to make it yours — legally.

You’ve found the perfect brand name. It’s clever. Catchy. The domain is available. The branding agency loves it. You’re ready to roll.

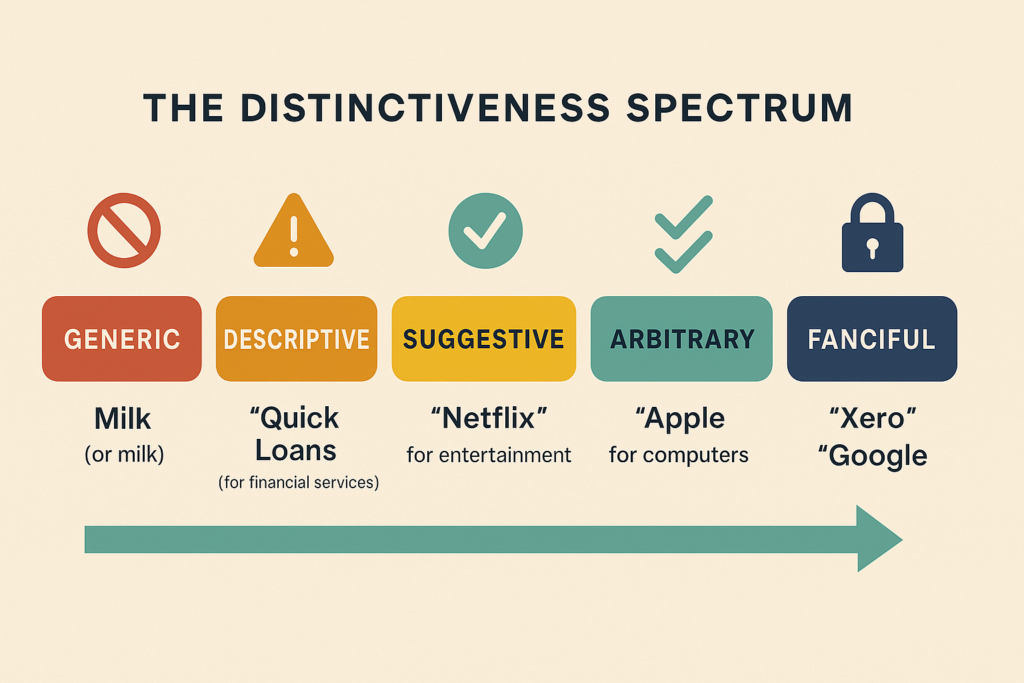

You’ve found the perfect brand name. It’s clever. Catchy. The domain is available. The branding agency loves it. You’re ready to roll. Not every brand name is created equal. In the eyes of the law, the more descriptive your mark, the weaker your rights.

Not every brand name is created equal. In the eyes of the law, the more descriptive your mark, the weaker your rights.