When Cheaper Medicines Meet Patent Law: Regeneron v Sandoz

A Federal Court decision has just reshaped the battlefield for biosimilars in Australia.

A Federal Court decision has just reshaped the battlefield for biosimilars in Australia.

In Regeneron v Sandoz [2025] FCA 1067, Justice Rofe refused an interlocutory injunction that would have blocked the launch of Sandoz’s aflibercept biosimilar. The case isn’t just about patents — it’s about the balance between innovation, public health, and billions in PBS spending.

The dispute

-

Regeneron and Bayer own patents over aflibercept (marketed as EYLEA®).

-

Sandoz sought to launch a competing biosimilar.

-

The Court was asked to stop the launch pending trial.

The ruling

-

No injunction: Justice Rofe refused to grant interlocutory relief.

-

Key reasons:

-

Public interest: cheaper biosimilars mean lower PBS prices, better access for patients.

-

Commercial realities: Regeneron had already launched an 8mg product (EYLEA HD), while uptake of Roche’s VABYSMO® was rising.

-

Patent merits: while Regeneron had arguable claims, they weren’t strong enough to outweigh the public health case.

-

Why it matters

-

For innovators: You can’t assume automatic injunctions — public interest now weighs heavily.

-

For biosimilar entrants: The Court is more receptive to arguments about affordability and patient access.

-

For the PBS: This case signals a judicial awareness of pricing impacts, not just patent rights.

Takeaway

This is one of the clearest recent examples of the Federal Court weighing patent exclusivity against healthcare economics.

Expect more disputes like this as Australia’s biosimilar pipeline grows.

Scidera v MLA and the Offshore Method Problem

Scidera v MLA and the Offshore Method Problem How long can a successful patentee delay the choice between damages and an account of profits?

How long can a successful patentee delay the choice between damages and an account of profits? If you thought plumbing valves were boring, think again.

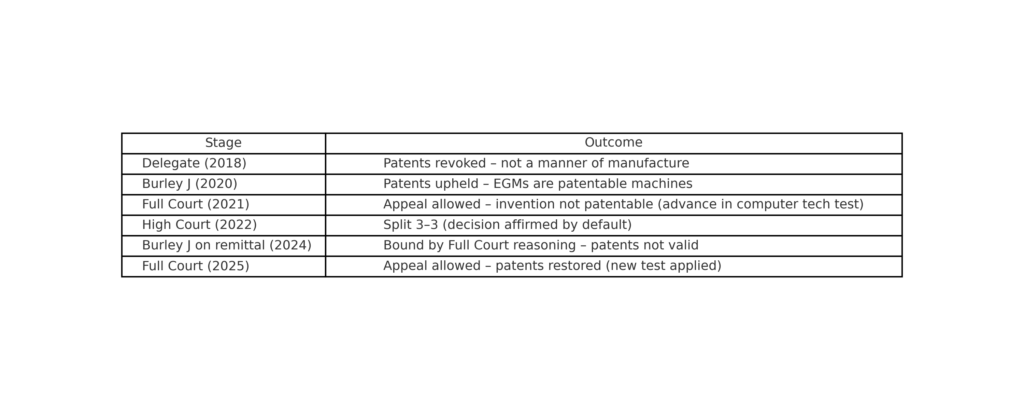

If you thought plumbing valves were boring, think again. When does a slot machine cross the line from an abstract idea to a patentable invention?

When does a slot machine cross the line from an abstract idea to a patentable invention?  Cue the latest appeal.

Cue the latest appeal.