Deepfakes on Trial: First Civil Penalties Under the Online Safety Act

The Federal Court has handed down its first civil penalty judgment under the Online Safety Act 2021 (Cth), in eSafety Commissioner v Rotondo (No 4) [2025] FCA 1191.

The Federal Court has handed down its first civil penalty judgment under the Online Safety Act 2021 (Cth), in eSafety Commissioner v Rotondo (No 4) [2025] FCA 1191.

Justice Longbottom ordered Anthony (aka Antonio) Rotondo to pay $343,500 in penalties for posting a series of non-consensual deepfake intimate images of six individuals, and for failing to comply with removal notices and remedial directions issued by the eSafety Commissioner.

Key Points

1. First penalties under the Online Safety Act

This is the first time civil penalties have been imposed under the Act, making it a landmark enforcement case.

The Commissioner sought both declarations and penalties, with the Court emphasising deterrence as its guiding principle.

2. Deepfakes squarely captured

The Court confirmed that non-consensual deepfake intimate images fall within the Act’s prohibition on posting “intimate images” without consent.

Importantly, it rejected Rotondo’s submission that only defamatory or “social media” posts should be captured.

3. Regulatory teeth and enforcement

Rotondo received notices under the Act but responded defiantly (“Get an arrest warrant if you think you are right”) before later being arrested by Queensland Police on related matters.

His lack of remorse and framing of deepfakes as “fun” aggravated the penalty.

4. Platform anonymity

Although the Commissioner did not object, the Court chose to anonymise the name of the website hosting the deepfakes — reflecting a policy judgment not to amplify harmful platforms.

That said, the various newspapers reporting on this story all revealed the website’s address, but noted it has now been taken down.

IP Mojo is choosing not to reveal that website.

5. Civil vs criminal overlap

Alongside the civil penalties, the Court noted criminal charges under Queensland’s Criminal Code.

This illustrates how civil, regulatory and criminal enforcement can run in parallel.

Why It Matters

-

For regulators: This case confirms the Act has teeth. Regulators can secure significant financial penalties even where offenders are self-represented.

-

For platforms: The Court’s approach signals that services hosting deepfakes are firmly in scope, even if located offshore.

-

For the public: The judgment highlights the law’s adaptability to AI-driven harms — and sends a clear deterrence message.

-

For practitioners: Expect more proceedings of this kind, particularly as the prevalence of AI-generated abuse grows.

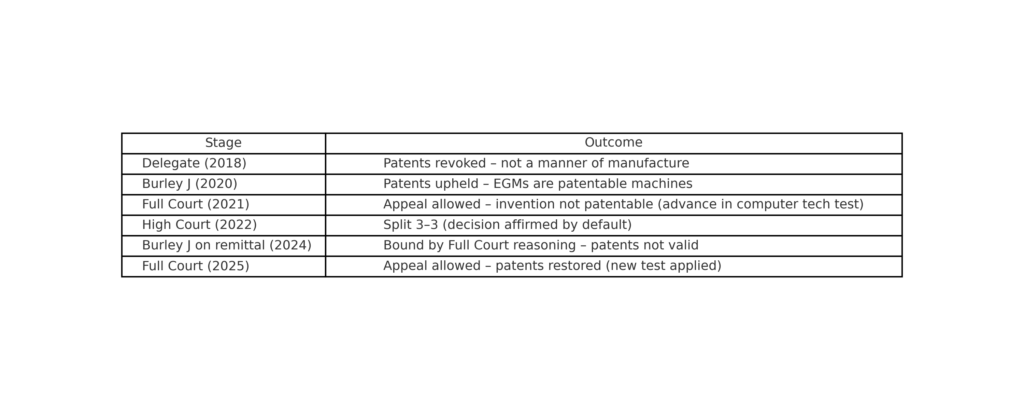

When does a slot machine cross the line from an abstract idea to a patentable invention?

When does a slot machine cross the line from an abstract idea to a patentable invention?  Cue the latest appeal.

Cue the latest appeal. When Epic Games went head-to-head with Apple, the Federal Court found that Apple misused its market power by locking iOS developers into the App Store and its payment system. That was big. But the Anthony v Apple class action takes it a step further: what if Apple has been overcharging Australian developers and consumers for years?

When Epic Games went head-to-head with Apple, the Federal Court found that Apple misused its market power by locking iOS developers into the App Store and its payment system. That was big. But the Anthony v Apple class action takes it a step further: what if Apple has been overcharging Australian developers and consumers for years? When Epic Games took on Apple in the US and Europe, the headlines practically wrote themselves – it was billed as a David-and-Goliath showdown between the Fortnite maker and the Cupertino colossus. Now, the same fight has reached Australian shores — and the Federal Court has bitten into Apple’s walled garden.

When Epic Games took on Apple in the US and Europe, the headlines practically wrote themselves – it was billed as a David-and-Goliath showdown between the Fortnite maker and the Cupertino colossus. Now, the same fight has reached Australian shores — and the Federal Court has bitten into Apple’s walled garden. As AI capabilities become standard fare in SaaS platforms, software providers are racing to retrofit intelligence into their offerings. But if your platform dreams of becoming the next ChatXYZ, you may need to look not to your engineering team, but to your legal one.

As AI capabilities become standard fare in SaaS platforms, software providers are racing to retrofit intelligence into their offerings. But if your platform dreams of becoming the next ChatXYZ, you may need to look not to your engineering team, but to your legal one. Imagine this: you take a screenshot of your favourite SaaS dashboard, upload it to a no-code AI tool, and minutes later you have a functioning version of the same interface — layout, buttons, styling, maybe even a working backend prototype. Magic? Almost.

Imagine this: you take a screenshot of your favourite SaaS dashboard, upload it to a no-code AI tool, and minutes later you have a functioning version of the same interface — layout, buttons, styling, maybe even a working backend prototype. Magic? Almost.