Sportsbet’s “More Places”: Distinct Enough to Register

Can a trade mark like MORE PLACES really distinguish betting apps and wagering services? The Registrar thought so in Sportsbet Pty Ltd [2025] ATMO 195.

Can a trade mark like MORE PLACES really distinguish betting apps and wagering services? The Registrar thought so in Sportsbet Pty Ltd [2025] ATMO 195.

The case was a test of s 41 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), which stops marks that are too descriptive from being registered. Examiners had argued that MORE PLACES was purely descriptive — suggesting Sportsbet’s services were available from more venues, or that gamblers could win more “places” in a race. Either way, they said, other traders needed that phrase free for honest use.

But Sportsbet pushed back. The Delegate agreed that while the words had a meaning, they weren’t directly descriptive of the goods and services. Instead, the phrase was more of a “covert or skilful allusion” in the Cantarella sense — an allusive tagline, not a generic description.

👉 Outcome: application accepted for registration.

Why it matters

-

Allusion vs description: This case shows how fine the line is between a mark that merely hints and one that directly describes.

-

Taglines can stick: Even in a heavily regulated, crowded industry like wagering, a catchy phrase can clear the s 41 hurdle.

-

The presumption of registrability is real: unless the Registrar is satisfied the mark can’t distinguish, applicants get the benefit of the doubt.

The takeaway? You don’t need a completely fanciful word to succeed. Sometimes, a clever phrase like MORE PLACES will do the trick.

If you’ve ever stacked a dishwasher, you’ll know the iconic Finish red “powerball” capsule. Reckitt tried to lock down that look with two shape/colour trade mark applications — but Henkel (maker of rival dishwashing products) opposed.

If you’ve ever stacked a dishwasher, you’ll know the iconic Finish red “powerball” capsule. Reckitt tried to lock down that look with two shape/colour trade mark applications — but Henkel (maker of rival dishwashing products) opposed. When Tiger Woods launched his new Sun Day Red brand with TaylorMade, it came with a sleek “leaping tiger” device mark. Puma — owner of the iconic leaping cat logo used since 1968 — wasn’t impressed.

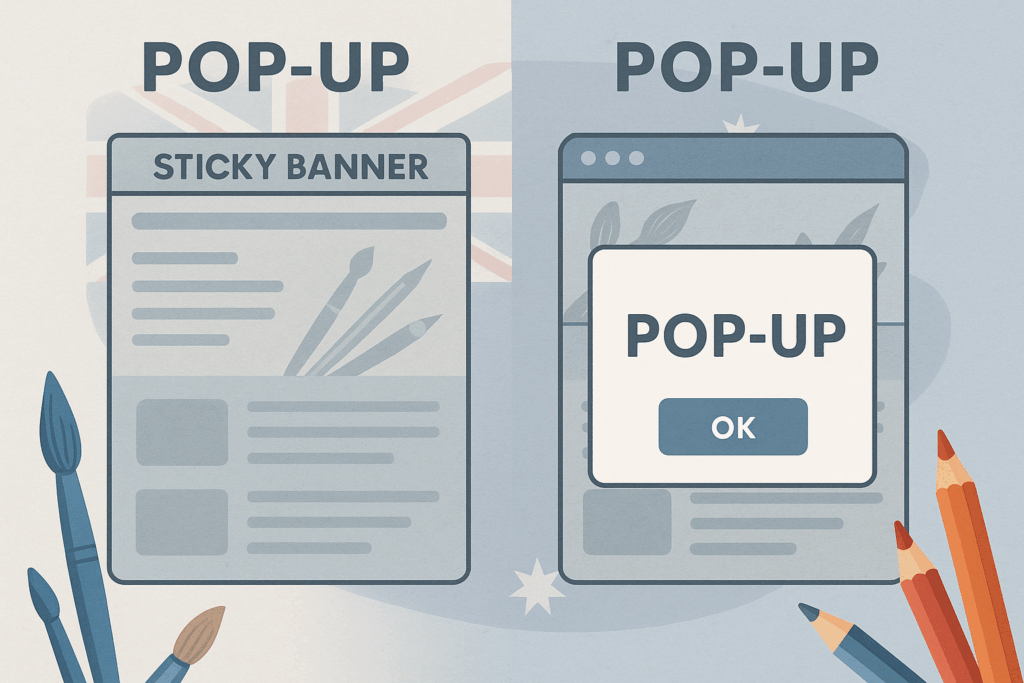

When Tiger Woods launched his new Sun Day Red brand with TaylorMade, it came with a sleek “leaping tiger” device mark. Puma — owner of the iconic leaping cat logo used since 1968 — wasn’t impressed. When two businesses with nearly identical names lock horns, things usually come down to trade marks, passing off, and reputation. But in Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd v Jackson’s Art Supplies Ltd (No 2) [2025] FCA 1127, the real fight was over disclaimers, pop-ups, sticky banners, and user attention spans.

When two businesses with nearly identical names lock horns, things usually come down to trade marks, passing off, and reputation. But in Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd v Jackson’s Art Supplies Ltd (No 2) [2025] FCA 1127, the real fight was over disclaimers, pop-ups, sticky banners, and user attention spans. If your brand is built on praise, don’t be surprised when you can’t block others from using it.

If your brand is built on praise, don’t be surprised when you can’t block others from using it.