Energy Drinks, Trade Mark Battles and a Bunch of Bull

If there’s one thing Red Bull hates more than caffeine-free soft drinks, it’s brand drift. And the latest target of its energy-charged enforcement? A would-be beverage mark from China: SeaBull.

If there’s one thing Red Bull hates more than caffeine-free soft drinks, it’s brand drift. And the latest target of its energy-charged enforcement? A would-be beverage mark from China: SeaBull.

In a decision handed down on 5 June 2025, a delegate of the Registrar refused Shandong Fokun Investment Co’s SeaBull trade mark application — finding it deceptively similar to Red Bull’s registered trade marks under s 44 and reg 4.15A of the Trade Marks Act 1995.

The result? SeaBull joins the long list of Red Bull casualties. When it comes to any other “bull” in the beverage ring, Red Bull’s horns are always up.

The trade mark at issue was the simple word mark SeaBull applied for by Shandong Fokun Investment Co., Ltd on 10 November 2022 in class 32 for non-alcoholic drinks including energy drinks.

The applicant claimed “marine extract” inspiration for the name and tried to distance itself from any reference to Red Bull.

Nice try.

Red Bull’s opposition strategy was as charged as their drinks:

-

Reputation: Global market leader, sold in 174 countries, with a dominant presence in Australia since 1999.

-

Evidence: Brand Finance rankings, Aussie revenue and market share stats, and an empire of media assets — from Red Bull Racing to Red Bull Records.

-

Registrations: Relied primarily on IR 1566986 — a stylised BULL mark registered for Class 32 beverages.

The delegate found that, although the competing marks were not substantially identical:

“The suffix ‘Bull’ is identical in substance… aurally, it comprises one of only two syllables… visually, the word ‘Bull’ is emphasised.”

While the addition of the word Sea tried to add a salty twist, it didn’t do enough to dilute the central BULL impression. The delegate found:

-

Consumers are likely to read it as Sea + Bull (not a singular new word).

-

“Bull” remains the essential, memorable element.

-

Conceptually, SeaBull still evokes the idea of a bull — not something distinct enough to overcome the similarities.

The outcome: Real and tangible risk of confusion → Ground under s 44 established.

The applicant didn’t bother to show up to the hearing and didn’t provide evidence of honest concurrent use, prior use, or other extenuating circumstances. That made the path to refusal even smoother.

It’s difficult to win a case when you don’t adduce any evidence and don’t show up – just saying …

Red Bull won the case and, of course, received an order for its costs too.

🧠 IP Mojo Takeaways

-

Adding a prefix won’t save you if the remaining mark is dominant and matches a well-known trade mark.

-

Red Bull’s enforcement strategy isn’t just for copycats — even marginal similarities to the word BULL in Class 32 can trigger a full opposition.

-

For global brands, consistent evidence of market presence, brand diversification, and registered rights are still the gold standard in trade mark opposition proceedings.

In the end, the only thing SeaBull gave Red Bull was another notch on its IP enforcement belt. For smaller beverage players looking to carve out their own brand, the message is clear:

Don’t poke the bull.

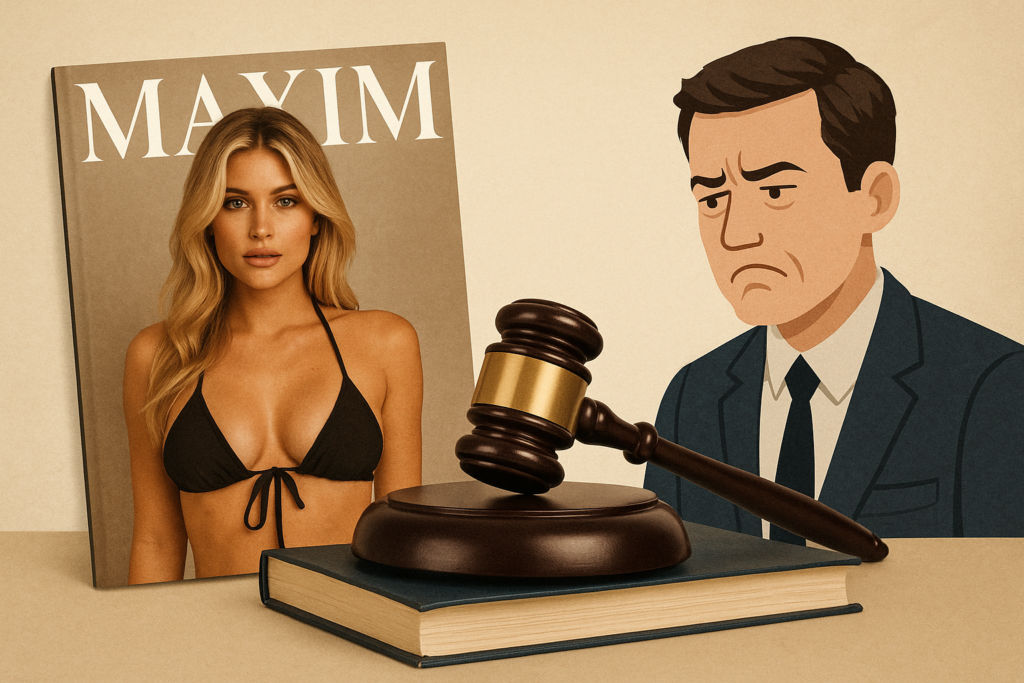

Maxim Media, the publishers behind the well-known men’s lifestyle magazine and brand MAXIM, had minimal success when in Maxim Media Inc. v Nuclear Enterprises Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1443 they sought urgent Federal Court orders to shut down an Australian company allegedly riding on their name — through magazines, domain names, destination tours, and model management services.

Maxim Media, the publishers behind the well-known men’s lifestyle magazine and brand MAXIM, had minimal success when in Maxim Media Inc. v Nuclear Enterprises Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1443 they sought urgent Federal Court orders to shut down an Australian company allegedly riding on their name — through magazines, domain names, destination tours, and model management services. So you’ve filed a series trade mark in Australia. The marks are visually identical except for a single word that tweaks the service type — say, “BURST PLUMBING”, “BURST CLEANING”, “BURST GARDENING”.

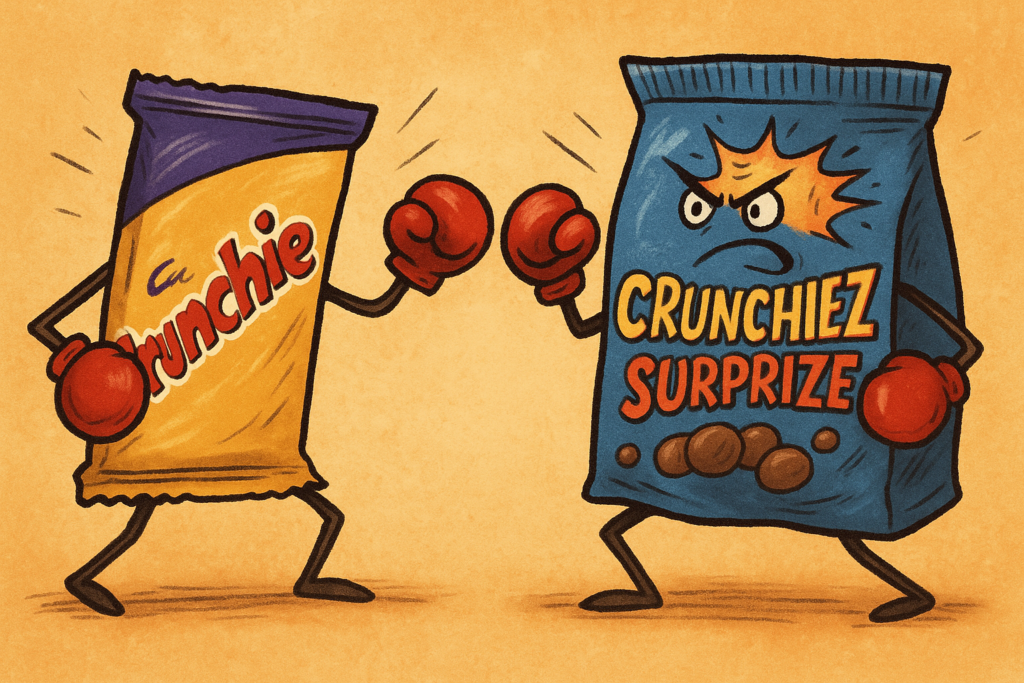

So you’ve filed a series trade mark in Australia. The marks are visually identical except for a single word that tweaks the service type — say, “BURST PLUMBING”, “BURST CLEANING”, “BURST GARDENING”. In a sweet victory for brand owners, Cadbury UK Limited has successfully opposed the registration of the trade mark CRUNCHIEZ SURPRIZE in Australia, convincing the Trade Marks Office that the name was too close for comfort to its iconic CRUNCHIE mark.

In a sweet victory for brand owners, Cadbury UK Limited has successfully opposed the registration of the trade mark CRUNCHIEZ SURPRIZE in Australia, convincing the Trade Marks Office that the name was too close for comfort to its iconic CRUNCHIE mark. What happens when your new brand smells a little too much like the towels next door?

What happens when your new brand smells a little too much like the towels next door?